Four fears keeping you from becoming a consultant – and how to overcome them

Stop talking yourself out of a rewarding career change, and start believing in what you have to offer

Stop talking yourself out of a rewarding career change, and start believing in what you have to offer

This article is from our community spotlight section, written by and for our journalism community.

We want to hear about your challenges, breakthroughs and experiences. Want to contribute? Get in touch and help shape the discussion around the future of journalism.

Independent consulting is becoming an increasingly attractive path in our industry. Some of us want more freedom. Others want to futureproof their careers. Many simply want to use their expertise in ways that feel more meaningful.

Yet in dozens of conversations with journalists, audience practitioners and others, I hear the same hesitation:

"I'd love to go independent… but I don’t think I’m ready."

I can relate. I wanted to become a consultant for years – but it wasn’t until last year that I finally pulled the trigger, dedicated time for consulting work, and started identifying as a consultant.

Why the delay? For a long time, I also didn’t believe I was ready. Because my risk-averse brain couldn’t get past four major challenges:

Maybe you share some of them? Here’s how I worked through each of these challenges, and what might help you do the same.

Some knowledge is not visible to you but visible to others

Many of us think we aren’t good enough to do consultancy because the expertise we have is simply not visible to us.

More than 15 years ago, at Nature Publishing Group, I was asked to oversee their blog network. I immediately said no because I didn’t think I had the authority or the knowledge to steer such a project. A few days later, the managing editor pulled me aside and said:

"Your knowledge may be invisible to you – but it’s visible to everyone else."

She was right. I was already recruiting guest bloggers, helping some bloggers structure their ideas into blog posts, and promoting their work. I had the knowledge. I eventually took on the responsibility. And it set me on the path to journalism, and what I do today.

Much of the expertise we have is not visible to us but is certainly visible to people around us. Think about the things colleagues thank you for explaining, the workflows you fix, the lightbulb moments you naturally create in conversations.

You already have valuable knowledge. You just need to take a step back, allow yourself to witness it, and acknowledge it.

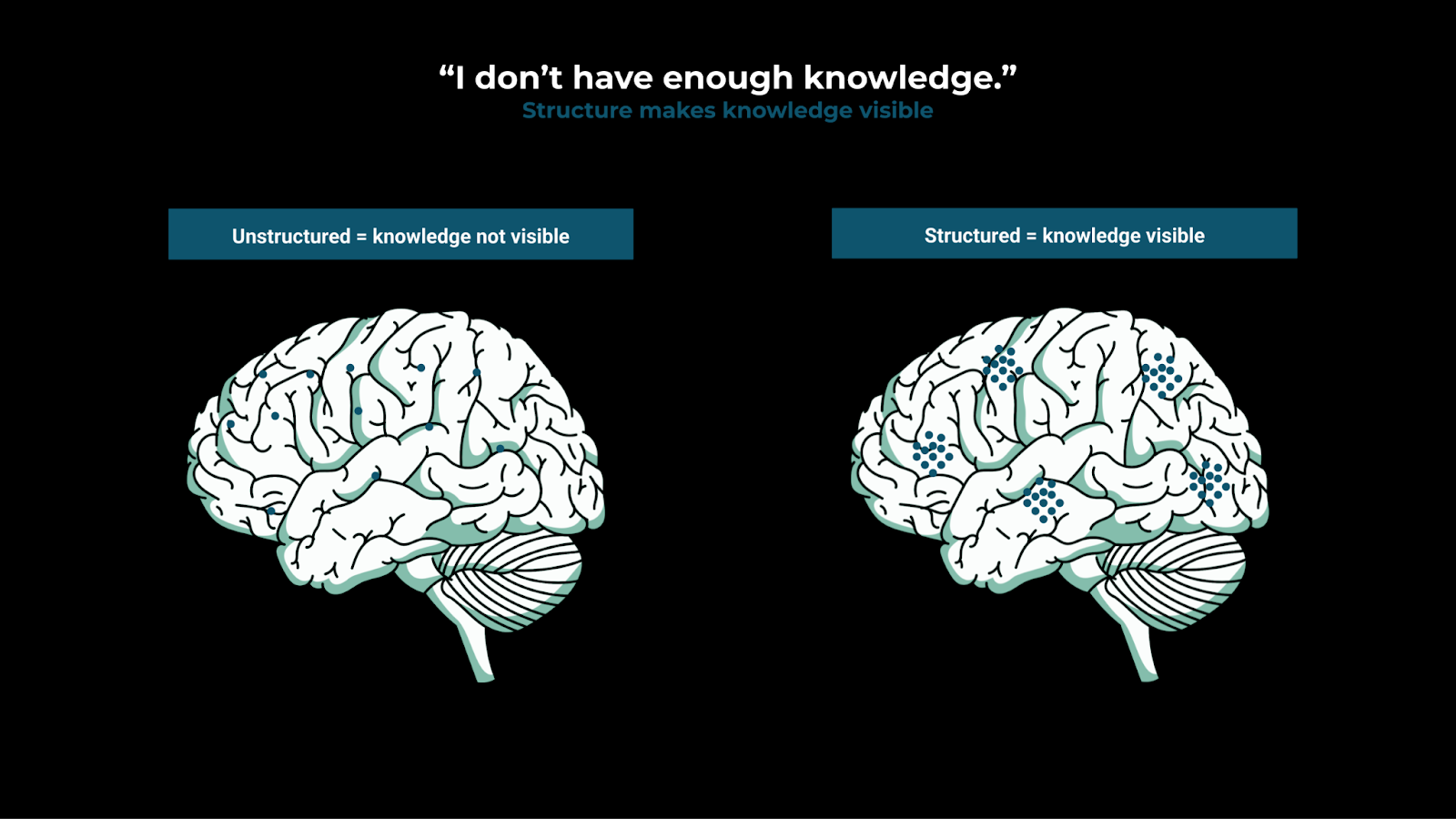

Some knowledge is not visible to you, and not visible to others … yet

That said, you probably also have expertise that is not visible to both others and yourself. Simply because it’s unstructured.

Your knowledge becomes visible when you structure it, when you consolidate scattered information in your head.

I consume sector content obsessively: articles, podcasts, newsletters, research reports … For a long time, all of the reading and listening was frankly worthless because I’d either not remember stuff or never find the right notes to refer back to. There was no structure.

The turning point was discovering personal knowledge management and building a "Second Brain": a system for capturing ideas, organising them, distilling them into new insights, and expressing them whether in reports, presentations, or social media posts.

My Second Brain has changed my professional life. It provides structure for the information I’m consuming. That structure allows me to consolidate the information into new knowledge, which I then share with my clients.

Practical takeaways

Many of us are introverts. Many often find traditional “networking” awkward or transactional. Many live far from media hubs.

I feel all of those. I’m not a natural conversationalist. I am too self-conscious to approach people I’ve never met at events. And those events are not especially accessible either – I live in Mauritius, far from London, New York or Singapore (but never far from the ocean).

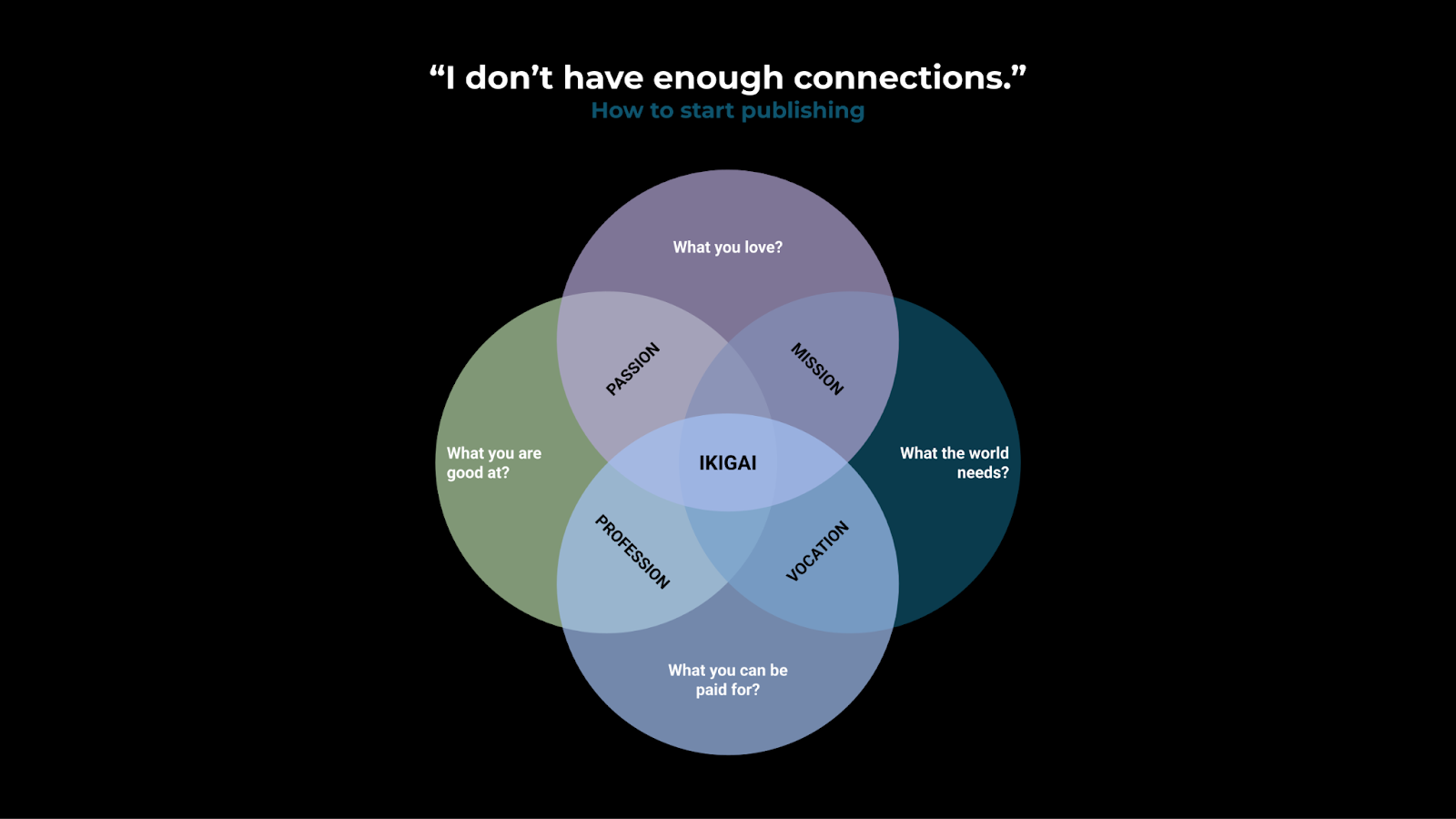

Still, I've built many meaningful connections over the years. By sharing knowledge.

I started posting on LinkedIn regularly three years ago. I noticed at the time that a lot of the insights shared within our industry came from large legacy organisations. Inspirational, but often not relatable to smaller and medium-sized newsrooms. So, I began posting practical insights, especially ones that would support smaller teams creating value for their audiences.

People started finding me and following me. Fast forward to today: I don’t have a massive following but what I do have is a community of peers who validate, challenge, and amplify my insights. Visibility grew but most importantly, trust density grew. Some connections have become friendships. Some have turned into collaborations or client relationships.

The lesson is this: you don’t network your way out of obscurity – you publish your way out of it. Sharing valuable content creates a surface area for serendipity and builds reputation that scales beyond geography.

Practical takeaways

Between newsroom deadlines, family responsibilities, and everything else, this is a very real concern. And when time feels scarce, any new aspiration – like starting an independent practice – feels impossible.

I've been through periods where being “busy” drained all my energy and creativity. There was this one time, during a particularly overwhelming period, I was wallowing in self-pity in the car with my dad. He listened, then asked me whether I’d considered taking a project management course.

I snapped back: “I don’t have enough time!"

But the suggestion stuck with me (as do so many of his suggestions). So, I took the course. By blocking just one hour a day for it. Six months later, I finished and gained tools that still shape my consulting work today.

Finding one hour a day seemed possible for me. But if that’s too much for you, then try half-an-hour, or even 15 minutes. I coached someone who aspired to start her own practice but already felt swamped. She was working ten-hour days and helping her parents with household chores. She agreed that finding 10 minutes daily was doable. Two weeks later, she upped it to 15 minutes. Two months later, she had her first two clients.

The point is this: create systems, or be enslaved by others’ systems.

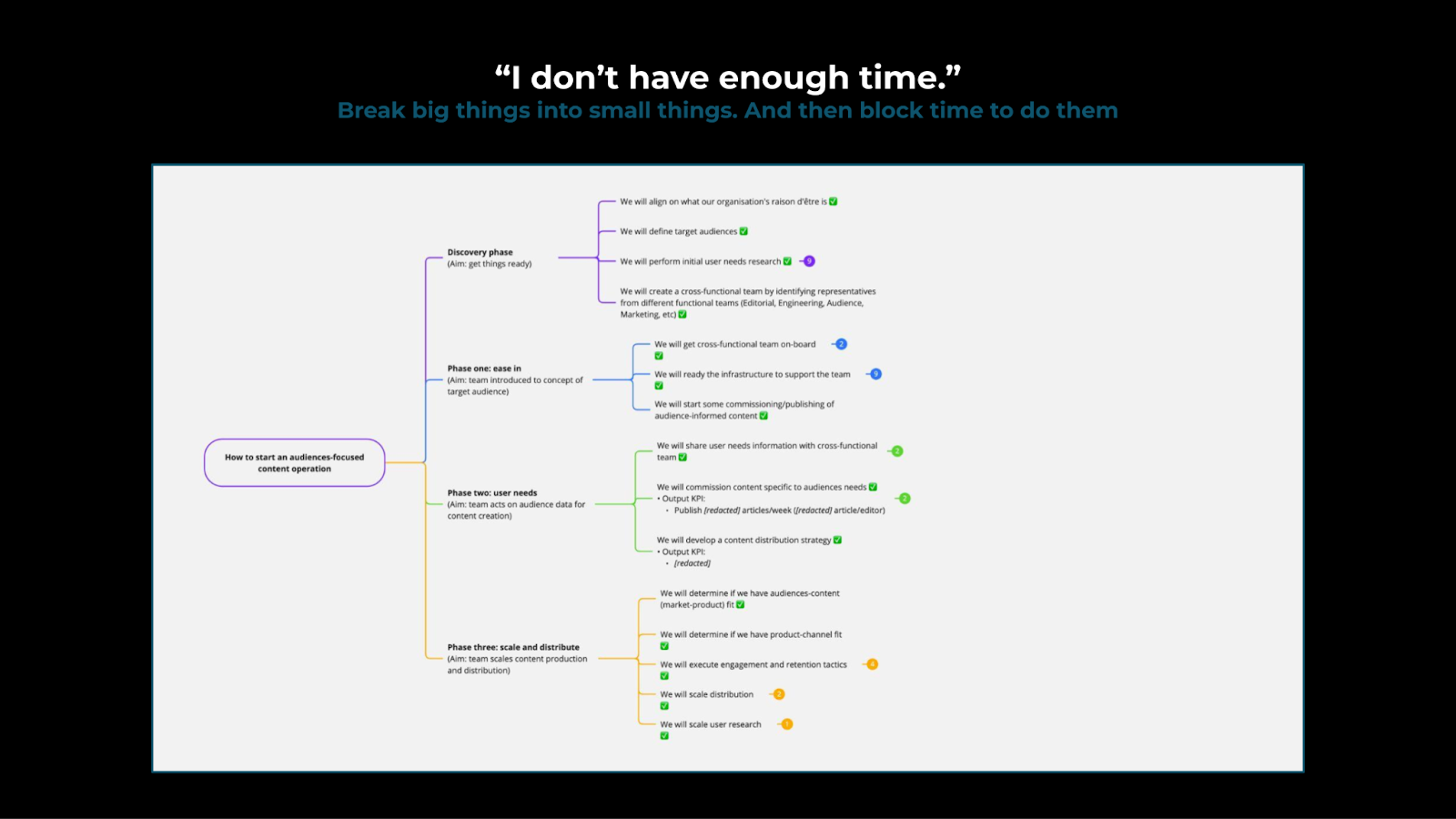

And break big things into small things that fit into the time you block.

The project management course was a big endeavour but it broke down into modules and chapters I could then fit in my system. That person I coached was overwhelmed by the enormity of starting her own practice, so we broke it down into smaller and smaller work packages – steps she could tick off within her system.

The first time I helped a newsroom implement the user needs model, the project seemed huge, messy, impossible to hold in my head. So, I broke it down into tiny steps. Those steps became the first version of the user needs playbook my clients now use.

Practical takeaways

Even when people overcome the first three fears, this final one often keeps them from taking action. We often imagine our first offering must be clear and perfect from day one.

It doesn’t.

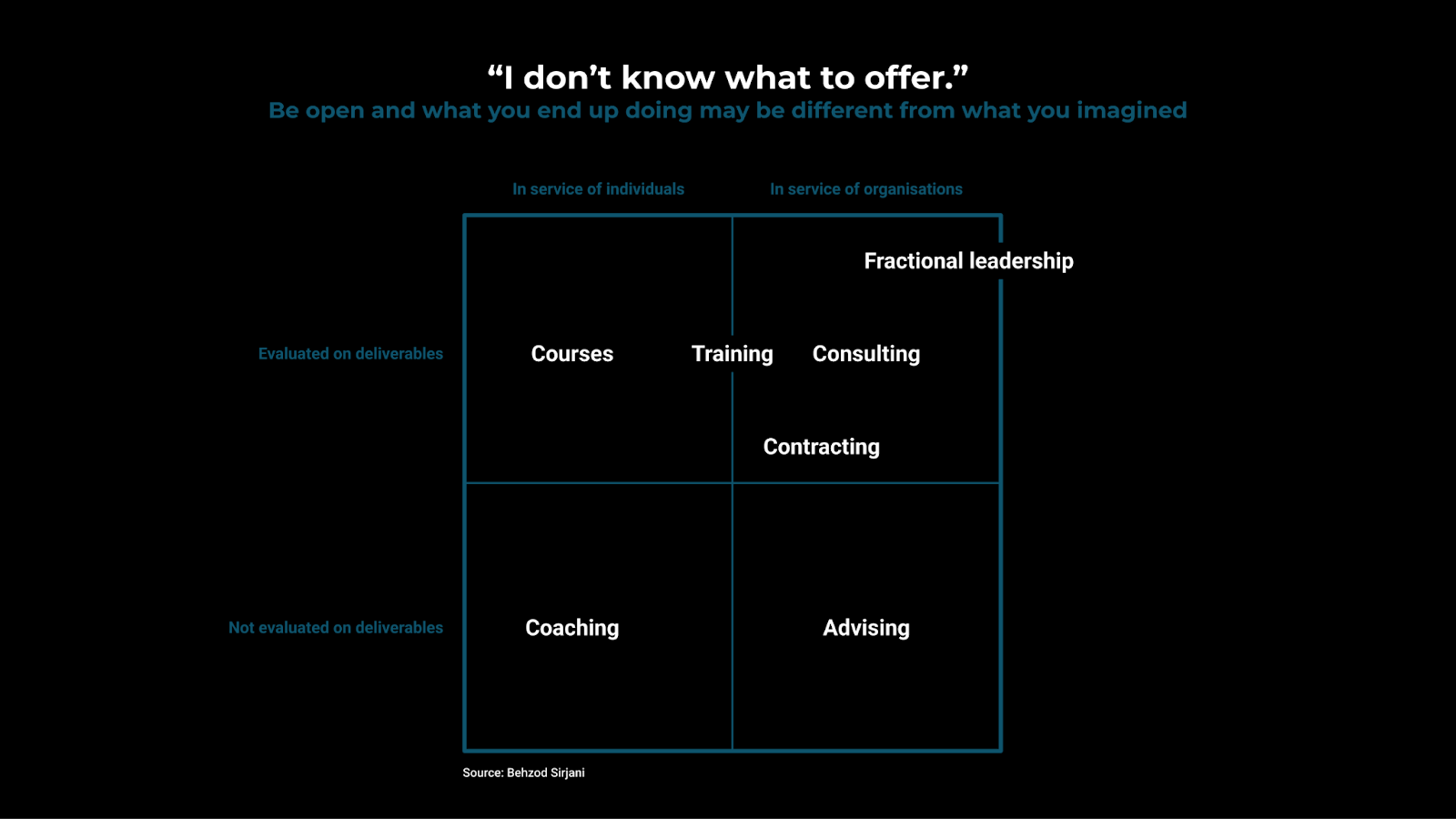

When I became a consultant, I assumed my work would revolve around implementing the user needs model through my playbook. But the more I worked with teams, the more I realised the playbook was incomplete. For example, many organisations didn’t have the necessary clarity about their purpose to implement user needs efficiently. Others were unsure whether they should prioritise all user needs or just a few.

To respond to those challenges, I created collaborative exercises and started facilitating teams to create clarity and enhance their decision-making. Over time, this became a part of my offering.

What I learned is this: the first offer emerges through doing, not overthinking. Consider each offer – especially the first one – as an experiment. It doesn’t have to be perfect. It can’t be perfect. But it will get better when you try it with real people.

Treating the offer as an experiment gives you permission to actually launch something. And it helps you adopt a growth mindset: you’ll always be open to feedback and opportunity, continually adapting and iterating, improving the offer gradually and consistently.

I found this growth mindset also made it easier to stretch myself and provide services I never thought I had aptitude for. After a few months as a consultant, I was facilitating, mentoring, coaching, and doing even more public speaking.

What I took from this is: the shape of your independence isn’t fixed, it’s a choice. Be open to the choices when they present themselves – because they will.

Practical takeaways

If you take anything from this piece, let it be this: you have knowledge, you can create connections, you don’t need huge amounts of time, and you hone your value by experimenting.

Start small. Structure what you know. Share generously. Break big things down. Experiment early. And you’ll find you’re much closer to independence than you realise.

Khalil is an advocate for audiences-driven approaches and an expert in audience development. He consults, advises, and mentors teams and individuals at media organisations worldwide, helping them shape stronger, more connected societies. He is also a public speaker and regularly shares insights on audiences-informed best practices on LinkedIn.