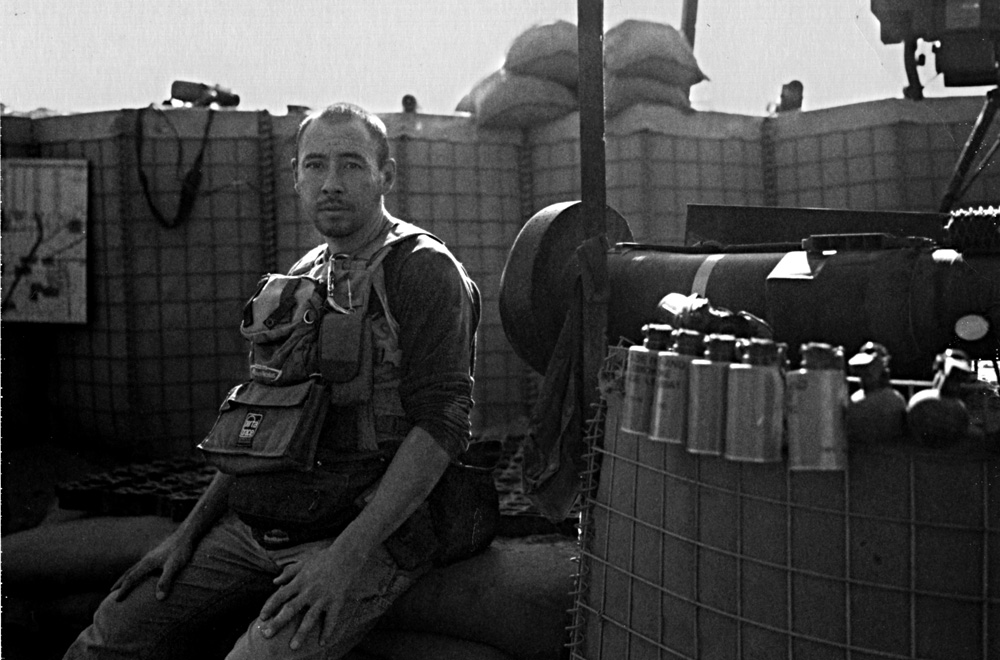

Teru Kuwayama is a photojournalist who has spent the last decade covering conflicts and humanitarian crises across countries including Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq. He recently won a Knight News Challenge grant of more than $200,000, to bring to life 'One-Eight', a project which will offer an online journal documenting the experiences of a US Marines troop in Afghanistan, including entries from the soldiers themselves. He talked to Journalism.co.uk about the importance of giving the world a direct window to life on the front line.

Why did you decide to enter the contest with this idea?

The Afghanistan conflict is now the longest war in US history. Like many of the Marines I'm working with, I've spent that decade cycling in and out of Afghanistan and Iraq, and Pakistan and Kashmir, and I've buried close friends there. It's very personal.

It's also a media issue. We've been in Afghanistan for a decade now, and yet the vast majority of Americans have a very limited sense of what we're doing there. That means we haven't been doing a very good job. We're now in a situation where our press is in serious decline, at a moment when our nation is escalating a war with tremendous costs. That means the public gets even more disconnected from its military, at a time when it should be the most concerned. I can't tell people what to think about this war, but I believe very strongly that they should be thinking about it.

Ask any soldier or Marine about coming home. One of the hardest stresses is the realization that so many at home are oblivious to the war they were sent to fight. I'm not talking about the friends and families of those servicemen and women, but a great number of Americans don't even know anyone who's over there. That's one of the side effects of an all-volunteer military, the direct experience of war falls on about one per cent of the population. A larger percentage is indirectly, but seriously impacted by separation from the people they care most about. But for most Americans, it's just a buzzing noise on the TV, or an endless stream of headlines that they've seen before, and that's how you get a "forgotten war".

How did you develop your idea?

I received a call out of the blue from a Marine officer I'd met six years earlier in the Korengall Valley in Eastern Afghanistan. I'd been embedded with his company of Marines, he'd had a positive experience working with me and he invited me to return to Afghanistan with his new battalion and he asked if I'd cover their entire deployment. I wrestled with the idea of how I could achieve a project of that scale, and I wondered what it would achieve? Who would actually pay attention to a year-long story about a battalion of Marines? Then it occurred to me that a thousand Marines could have a significant, and dedicated network of family and friends, that this project could serve them, and through social media networks and channels, they could push reports out to an even larger population.

I applied for a Knight News Challenge award, which supports digital media initiatives that target specific geographic audiences, partly to fill the void in smaller towns or cities, where local newspapers will be the first casualties of the collapse of the journalism industry. I proposed this project, to connect a Marine battalion in southern Afghanistan, with their community at home base North Carolina. I also had the support of the John S. Knight fellowship at Stanford university, which gave me time and resources to develop the concept, and a team of journalism fellows whose knowledge and experience I could draw from. At the same time that I received the News Challenge award, I was also selected as a TED Global fellow, which connected me with a tremendous reservoir of mind power, and an outpouring of encouragement and support.

What issues do you hope the idea will solve?

I don't know what problems I can solve in the short term, but the project will serve as an experiment, and a prototype for a different way of reporting. One of the complaints I heard from the military was about "drive-by journalism", where reporters who haven't bothered to learn the most basic things about the military, hop on-board for a few days or weeks, then crank out shallow, redundant reports that the subjects don't even see. From the journalists' side there's the frustration of risking their lives to produce images and reporting and seeing most of it end up on the cutting room floor.

There's also a trust deficit between the military and the media – and one of the successes of embedded journalism is the fact that it's cleared some stereotypes and built some relationships. I've got unusual access to the battalion, for the simple reason that there are Marines who know me and trust me. They don't expect me to be an uncritical cheerleader, but they can trust me to be honest, to be fair, and maybe most important, they trust me to pull my own weight, and not get them killed by falling apart when things get rough. This project is also going to introduce some young reporters to their counterparts in the military. We need to build these working relationships, because they aren't calling it "the Long War" for nothing and we can't count on the conventional media to get it together. We're going to have to do this ourselves, and I think we can do it better.

How did you feel when you found out you had won?

As the saying goes, "be careful what you ask for". In my case, I get a year in one of the most volatile places on Earth, so I have very mixed feelings. At the same time, I've been surprised, and touched by the amount of trust and support I've received. The first response I got was "I can't believe no one has ever done this before".

How soon will you start?

We're working on a very compressed timeline – a matter of weeks to get the project running before the battalion deploys. We're also working with very limited resources, and we're trying to pilot a model that others can replicate with even more limited resources. It has to be light, mobile, and highly adaptive to shifting conditions and technology, and it's going to rely on small numbers of unusually motivated, and autonomous operators. In that way, the transition from traditional media to new media, or "guerilla" media is going to have a lot of parallels to the conventional military's transition to counterinsurgency footing.

The primary expense will be internet connectivity from Afghanistan, and human resources. For everything else we're relying on free, open content management systems and sharing platforms.

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).

Related articles

- Ukrainian journalists are at a breaking point. It is time to make a change

- Six career lessons in war and conflict reporting

- Unveiling the lessons of a war reporter's journey, with Andrea Backhaus

- Why journalists risk their lives for a story, with Dr Anthony Feinstein

- Kyiv Independent launches an English-speaking journalism school