On a cold, dark, Thursday evening in November, media professionals and students at the University of Oregon’s School of Journalism and Communication gathered to discuss some of the lessons contained in a new book, Data Journalism: Inside the Global Future.

Edited by Tom Felle, John Mair and Damian Radcliffe, the volume looks at how journalists across the world are unlocking the possibilities data-driven journalism creates. The event included three presentations from contributors to the book, each offering a different perspective on the subject.

Damian Radcliffe, the Carolyn S. Chambers professor in journalism at the university, and also a co-editor of the book, provided an overview of the skills, case studies and considerations for the future highlighted by the publication.

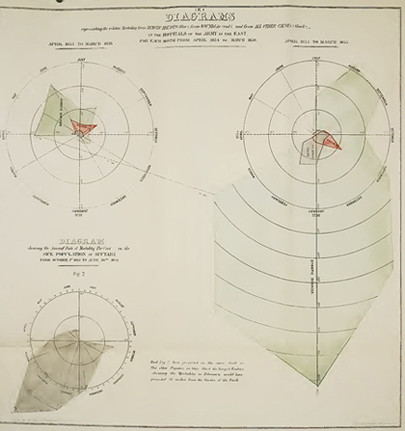

He cited Florence Nightingale, the Victorian physician John Snow, and the 19th century American newspaper editor Horace Greeley to remind attendees that data journalism has always been around. “But,” Radcliffe said, “the tools for creating data-driven journalism have never been better.”

One of his key takeaways from editing the book was “a recognition of the sheer range and volume of tools that we now have access to in order to create, analyse and visualise data.”

Graphic by Florence Nightingale, showing causes of mortality for British soldiers in the Crimea via the Guardian.

To code, or not to code, that is the question

The mainstreaming of data journalism is a trend that Steve Doig, Knight Chair at Arizona State University, has seen occur during his career.

“Being able to work with data…I guess that was sort of my superpower,” he said, reflecting on his early years as a journalist.

Doig, who participated in the event via Skype, brought home a Pulitzer Prize for his investigative work on the impact of Hurricane Andrew on property in South Florida in 1992. His analysis showed how poor construction of newer structures had contributed to the disaster.

Despite this work being produced using SAS software, and his own experience of working with code in a newsroom, Doig’s contribution to the book was a counter-argument to the idea that every journalism student should learn to code.

Only a minority of students are interested in coding, said Doig, who prefers to focus on ensuring students are proficient with spreadsheets and simple mapping programmes, whilst also showing them what’s possible and what’s out there.

“You need to know how programs work, but you don’t necessarily need to know everything about them,” he explained.

One reason for his approach is the complexity of this space and how quickly it changes. Doig pointed to the 1,700 languages used for different kinds of coding, and how the now virtually obsolete Flash – a mainstay of many journalism courses at one point – illustrates a constantly changing technological landscape.

'Visuals are absolutely more than just decoration'

The final speaker, Nicole Smith Dahmen, assistant professor of visual communication at the University of Oregon, made a passionate case as to why new, engaging forms of journalism matter.

“Visuals catch audience attention,” she said, and “are processed 60 times faster than text. They are a universal language, which engage and forge a human connection,” she argued – this “makes them an important element in journalism.”

To illustrate this, Dahmen highlighted a Washington Post infographic called The depth of the problem, which shows just how deep in the ocean the black box from Malaysia Airlines flight 370 could be.

She scrolled to 1,250 feet, the height of the Empire State Building; 2,600 feet, the depth of giant squids; 4,600 feet, where the signal was picked up; 12,500 feet, where the Titanic sits; to 15,000 feet, where the black box was believed to be.

“You’re not just reading how deep that plane is,” Dahmen said. “You can see and engage and really experience and understand how deep they suspect that plane to be.”

What this means for journalism schools

Radcliffe reminded audience members that “at the end of the day, data journalism is just a tool, and we’re still storytellers.” He stressed the importance of core skills – reporting, writing, media law, ethics and a strong news sense – whilst also noting that data journalism is an increasingly essential part of the modern journalist’s toolkit.

The panel’s enthusiasm for data-driven journalism was shared by many attendees.

“I really think it’s amazing what stories you can tell visually,” said Jenny Dean, a Ph.D. student. “And it’s amazing what you can do with big data and how you can make it palatable.”

Shan Anderson, instructor in advertising and digital publishing at the University of Oregon, was also interested in these emerging forms of journalism. “To see our school focus on it is a real advantage,” he said.

However, identifying the best way to teach this subject is an ongoing challenge for all journalism schools.

There was an animated discussion around Steve Doig’s anti-coding philosophy, whilst journalism and media studies doctoral student Irene Awino cautioned against making journalism too tech-driven. “How do we define journalism? Because if we’re not careful, a lot of it is going to be so technical,” she said.

“Visuals help us to craft better stories,” Dahmen added, echoing Radcliffe’s view that at the end of the day, journalists are still in the storytelling business.

“Data journalism is just another way to do this,” said Radcliffe. His hope “is that in a couple years' time, we won’t be talking about data journalism. It will just be journalism.”

August Frank and YingYing Yang are journalism majors at the University of Oregon's School of Journalism and Communication. Damian Radcliffe (@damianradcliffe) is the Carolyn S. Chambers professor in journalism at the University of Oregon and an honorary research fellow at the Cardiff School of Journalism, Media and Culture Studies.

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).