How to take your journalism from the page to the stage

It turns out that human stories and interactive theatre go hand-in-hand

It turns out that human stories and interactive theatre go hand-in-hand

This article is from our community spotlight section, written by and for our journalism community.

We want to hear about your challenges, breakthroughs and experiences. Want to contribute? Get in touch and help shape the discussion around the future of journalism.

Early next month, The Lebanon Displacement Diaries – a participatory journalism project we produced together at The New Humanitarian – will head to the stage in Beirut, where actors will voice the stories of people forced to flee their homes during Israel’s bombardment of Lebanon last year, and the audience will be able to share their own stories too.

It’s an exciting new move for the project, which was first published six months after the November 2024 Israel-Hezbollah ceasefire and shares the stories of 10 of the approximately one million people in Lebanon who were displaced over a year of war.

But it also feels like the natural next step in a journalistic practice that was designed to be a collaboration with Lebanese communities, and to acknowledge that when a war technically ends – or when a piece of reporting is published – the story isn’t over.

From the outset, our thinking about this project was coloured by the fact that Zainab’s (Chamoun, co-ordinator, right) family had to flee their south Lebanon home in September 2024, and the two of us were in near-constant contact during bombings, as she slept in overcrowded rooms and longed to return home and retrieve her beloved cat, despite the danger.

She wrote about that time in a piece for The New Humanitarian, and about the fact that displacement is more than just a technical term or a statistic, even when the numbers are startling: Some 82,000 people in Lebanon still can’t go home. The truth is that displacement is an all-encompassing emotional and physical event that impacts every part of a person’s life, and understanding that – which can really only come through lived experience – was an important backbone of how we collected and published these stories.

How do you even start to translate such a complex life experience onto the page? As we learned, it’s complicated. While a ceasefire was already in place when we began the project, Israel was still regularly bombing Lebanon (as is the case today), and we wanted to be sensitive to the fact that many people were dealing with various forms of ongoing trauma. That’s why we consulted a Lebanese therapist to work with us on a trauma-informed way of approaching the interviews.

We built a set of guidelines that made sure consent was truly informed. Participants could select where and when the interviews would take place. They were warned in advance that their stories would be cut down and translated into English, but also that they would have the opportunity to review the cuts to make sure they were not mischaracterised.

For the most part, these conversations were conducted in participants’ own first languages and with people – either Zainab or Lebanese journalist Ghadir Hammadi – who both spoke their language and had also experienced displacement. These commonalities can make a big difference in terms of the psychological toll of telling and hearing these stories, for both the journalists and the interviewees.

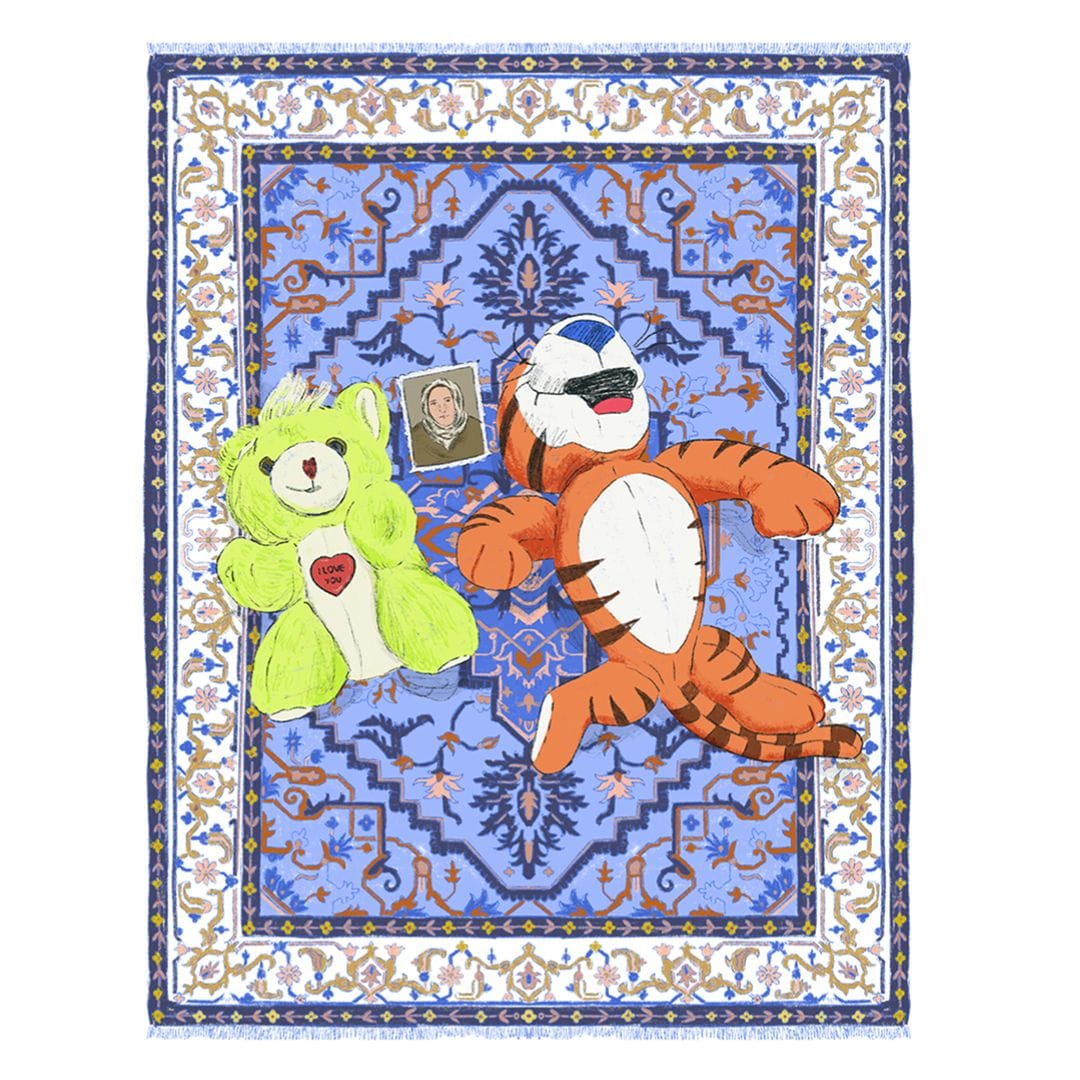

Crucially, the project’s translator Najat Keaik is also Lebanese, which meant she understood the importance of various dialects and regional turns of phrase. The Lebanese illustrator, Sasha Haddad, created illustrations for the project of items that were drawn from the conversations, and chosen by the participants themselves. They mostly show things they took with them when they were displaced, but in some cases they are of treasured places or memories.

We still checked facts and dates and inserted clarifications where needed, but as a wise colleague recently put it during a workshop we conducted on inclusive storytelling: This sort of participatory journalism sees “people as experts on their own lives”.

While it was tough to select a limited number of people to speak with in a country deeply impacted by war, we ended up choosing the final 10 for a variety of factors: religion, location, age, nationality, and gender. They also enthusiastically wanted to talk, and felt safe doing so. We tried to help this process by making it clear they could share what they wanted, including photos and videos, but they didn’t have to share imagery – or publish their real names – if they didn’t want to.

Over time, what emerged is a series of stories that we believe cuts through the narrative that a ceasefire is a magic button that brings things back to normal. It allows people who were displaced to be seen – both by their own divided society and by international readers – through more than headlines, short quotes, or military narratives.

The New Humanitarian reports on humanitarian crises as well as the aid industry, and one key theme that emerged from this project is that – even when asked directly – most people didn’t mention what we traditionally think of as aid, with the clear exception of shelter: While many people stayed in rented homes or with family and friends, others had to use community or NGO-run shelters.

What did come through as a true need, even when it was not explicitly said, was psychosocial support. The expectation that returning home is a cure-all is unrealistic, especially given that many people’s homes and villages no longer exist, thousands of people were killed, and drones are still flying overhead. People need help, but mental health support is often the first thing to go in an aid sector increasingly plagued by cuts.

All of this was an important reminder that journalists need to talk less, and listen more. The journeys of Abu Ali, Abbas, Hassan, Leo, Nour, Raghida, Riham, Robert, Zahraa, and Yasmina – of who they were before the war as well as during and after – would not have been so fleshed out if we had interviewed them for a short piece on displacement; if we had not asked them about their gardens, their pets, their fears, and even how the war smelled.

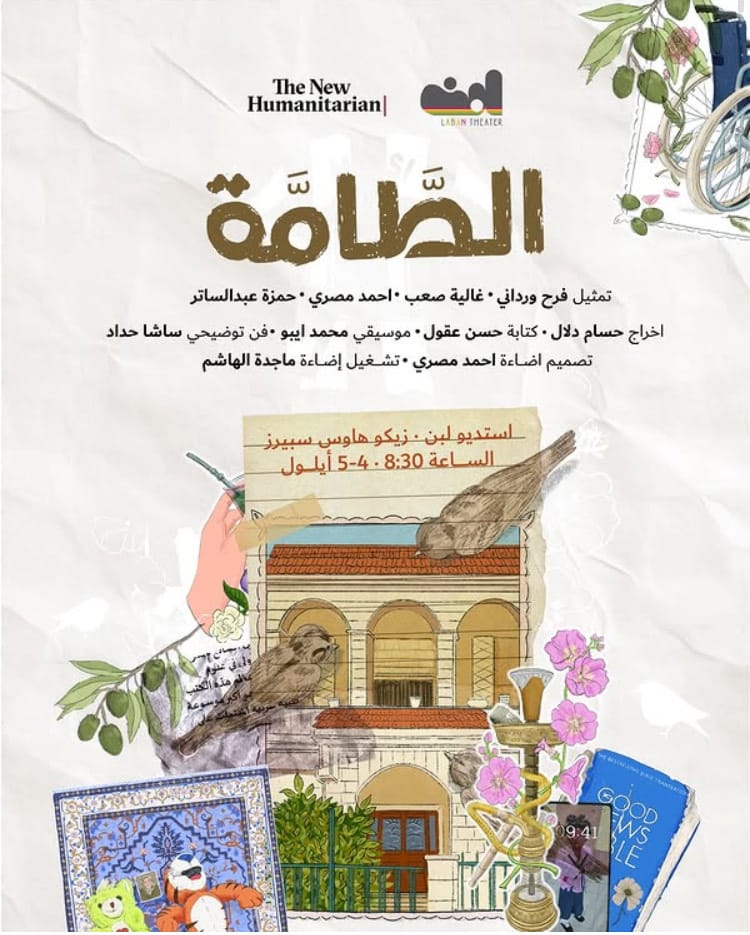

Their personal stories have changed and moved on after publication, as have the conversations about displacement and the war in Lebanon. The Beirut-based Laban Theater has now helped to expand The Lebanon Displacement Diaries into an Arabic-language play called Al-Tamma (“The Catastrophe”).

This production will allow even more people to interact with the subject matter, as audience members but also as people with their own stories to tell. Laban uses a technique called “playback theatre” – where audience members’ stories become part of the play, in front of their eyes.

Laban has created theatre about other traumatic events in Lebanon, and we trust them – as we have trusted our colleagues, artists, and storytellers on this project – to create a safe place where even more stories can be told. The way we see it, this is journalism and it is still participatory, it just looks a bit different on the stage.

Thank you for reading this community spotlight piece. These articles help shape the discussion around the future of journalism. Want to write one for us? We'd love to hear from you