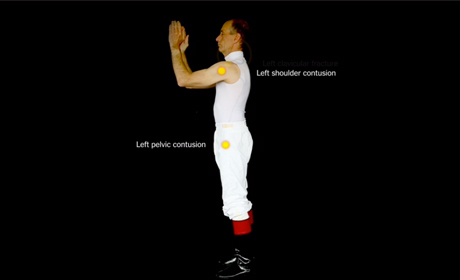

A still taken from one of the videos in The Jockey

Last week the New York Times website published a story called The Jockey, followed by publication in the sports section of the print edition on Sunday.

The Jockey is the latest immersive or multimedia reading experience created by the news outlet that brought us Snow Fall. The Jockey tells the story of Russell Baze, the first North American jockey to ride in 50,000 races, and does so through long-form text, video and moving graphics.

This immersive story has a sponsor. Some have interpreted this as native advertising or sponsored content, and AdAge writes that these custom ad units are "designed to better fit the new environment" than the advertising within Snow Fall.

In this feature we speak to Barry Bearak, the Pulitzer-prize winning journalist who wrote the story of The Jockey, and Steve Duenes, associate managing editor of the New York Times, to find out how long the project took, some of the storytelling choices made along the way, and more about the sponsor deal.

Writing The Jockey

Barry Bearak started working on the story of The Jockey in November. That was a month before Snow Fall was published and at that point there had been no decision taken to turn this into a multimedia story. And although work started at the end of last year, the idea for a profile piece on Baze had been around for some time.

The original idea came from Joe Sexton, the then sports editor (who is now at ProPublica), when he was trying to recruit Bearak to his team. Bearak was a foreign correspondent returning to the US and one of the ideas suggested by Sexton to Bearak was a profile piece on Russell Baze.

"Baze wasn't interested," Bearak told Journalism.co.uk, and the jockey again said no after Bearak tried to get the PR department at racing venue Golden Gate Fields to persuade him.I approached it exactly the same as I would have done without the videoBarry Bearak, reporter

Bearak "put it aside for a year" and then went back to Baze, again with the help of the PR department from the race track, and Baze said "he would reluctantly cooperate".

The journalist flew to meet the jockey and when he returned from the first trip, Sexton – who worked on Snowfall – made the decision "to go all out with a multimedia presentation", Bearak said.

"On subsequent trips Baze became increasingly comfortable with the process and more cooperative," Bearak said, and "he's now very appreciative" of the story being told.

Bearak had the "writing pretty much wrapped up in April" and produced the story no differently despite knowing it would have multimedia components.

"My part of this was fairly traditional," Bearak said. "I approached it exactly the same as I would have done without the video."

Going multimedia

Videographer and photographer Chang Lee was brought in and, along with graphics editor Xaquín GV, set up a complicated shoot, involving Baze wearing a miniature Pivothead camera on his goggles to provide point-of-view (POV) video footage, and 15 GoPro cameras around the track to capture the jockey racing.

A POV shot

The piece also includes a moving graphics explainer showing Baze's body and the many injuries he has sustained, created by graphics editor Graham Roberts.

Presentation

Work on the multimedia part of the project got underway "a couple of months in to 2013", Steve Duenes, associate managing editor of the New York Times told Journalism.co.uk.

Unlike most stories carried by news sites, The Jockey does not start with a headline. The reader is introduced to Baze with a short piece of text and then an autoplay video before the title appears, much in the way that a film title is often introduced after the first scene.

This was done to "allow the reader to get into the scene", Duenes explained.

As each section of text transitions to a video, the last paragraph is read aloud. Bearak provides the audio narration as part of the video to take the viewer through the shift from reading to viewing. When the viewer moves on to the next section of text after a video, he or she then sees the previous paragraph of the last written section, displayed in a grey rather than black to act as a visual guide.

Duenes explained that the decision was taken to create "a transition in a way that felt natural".

"We didn't want to rob readers of control," he said, so decided to give people the option to skip the videos.

The videos autoplay, in the same way as they do in the Guardian's multimedia project Firestorm and as moving graphics autoplay in Snow Fall. Asked whether the team were at all influenced by Firestorm, Duenes said those interested in this type of storytelling at the New York Times naturally pay attention to any "ambitious immersive projects" published, explaining that they "developed similarly but separately".

Story length

Blogging site Medium tells readers how long it is likely to take them to consume a story, much in the same way as video viewers on YouTube see the duration. And if the immersive experience borrows from film in others ways, has the New York Times considered putting a rough time guide on such multimedia presentations?

Duenes said there were frequent discussions about time and how long an immersive feature should be – the 17,000-word Snowfall takes a couple of hours; at 11,000 words The Jockey takes about an hour – but said the length was determined on a story by story basis.

Mobile and tablets

As with all of these multimedia presentations, mobile must be considered, particularly as long-form stories are often well suited to the lean-back experience of reading on a tablet device.

The solution was to carefully consider mobile and tablet consumption, as well as a range of browser types. The presentation appears slightly differently in each.

Figures

The New York Times told us it does not share stats on individual stories so it is not possible to say how many people have read The Jockey or the break down between on mobile, tablets or desktop.

Figures were shared for Snow Fall and reported by Jim Romenesko. Six days after publication of Snow Fall that story had received 2.9 million visits and 3.5 million page views, with up to 22,000 users at any given time. A quarter to a third of the hits were from new visitors to nytimes.com and average time on site was 12 minutes.

Eight months after publication and Snow Fall has been tweeted nearly 10,000 times and shared on Facebook more than 80,000 times.

At the time of writing, The Jockey has been shared more than 8,200 on Facebook and more than 900 times on Twitter.

The Jockey in print

The web presentation of The Jockey was published several days before it was published in print, with the website bringing it back to the homepage as it appeared in the newspaper on Sunday.

The "bold presentation", as Duenes described it, involved a full page photo on front of the sport section which requires readers to turn the broadsheet sideways. Images were displayed large, text was standard body copy and one of the videos, where the jockey narrates his own story over moving footage, became a print graphic.

Advertising and monetisation

When Journalism.co.uk interviewed John Branch, the journalist who wrote Snow Fall, he told us that Mark Thompson, chief executive of the New York Times (and former director general of the BBC), questioned the decision of including advertising within Snow Fall when he saw it, suggesting the advertising should have been omitted.

Om Malik, founder of GigaOM, wrote that sponsorship would have been a good solution to monetise Snow Fall, suggesting a brand such as Land Rover as a good fit to a story about an avalanche.

The Jockey is sponsored, with BMW adverts within the piece and branding throughout.

So is this a case of the story commissioned so that BMW could get its brand message out, or does this engaging type of story create additional sponsorship potential? Duenes said BMW was brought in much later in the process and although BMW representatives were given an idea of what the story was as the ad teams pitched to them, the sponsorship was sold after the story was commissioned and there was no influence on editorial.

Duenes said he was not aware as to whether the sponsorship deal covered the costs of production.

Unlike Snow Fall, which the New York Times made available as an ebook priced at $2.96 on Amazon and via a partnership with Byliner, and the Guardian which offered a more in-depth version of Firestorm available as a paid-for ebook, the Times has not tried to monetise The Jockey in this way.

The team

Along with reporter Barry Bearak, photographer and videographer Chang Lee, and Duenes's involvement, there were a number of other key people involved in producing the piece.

Duenes explained that Graphics editor Xaquín González Veira tracked down the goggle camera that Baze wore in actual races, and largely orchestrated the race video.

Video journalist Catherine Spangler was the central video editor on the project, and contributed many strong ideas for how the piece would be produced, according to Duenes.

Jon Huang was the main front-end developer and is also a graphics editor. "His elegant transitions from text to video were central to the piece," Duenes said.

Andrew Kueneman is the deputy digital design director and many of the ideas for how the project looked and worked were his. Graphics editor Graham Roberts designed and executed the video showing Baze's injuries and R Smith is a digital designer who helped shape the overall look and interaction strategy for the piece.

For more on the Snow Fall story see this feature. For more on the creation of Firestorm see this feature.

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).

Related articles

- From Reuters to The New York Times, Big Oil pays 'most trusted media brands' to push greenwashing

- Four digital media trends to watch: generative AI, Gen Z, business models and news formats

- UK journalism still has a problem with working class

- #MeToo inside the newsroom, with Jane Bradley and Lucy Siegle

- How to create viral news videos