The Associated Press, Guardian and satirical site The Onion have all had their Twitter accounts hacked by the Syrian Electronic Army within the past six weeks.

The Onion's Tech Blog explains exactly how their account fell victim to the hack, explaining how a phishing email was sent to various employees. What appeared to be a link to a Washington Post story directed victims to a separate URL requiring Google passwords before redirecting back to Gmail. The hacker then emailed colleagues' addresses from the phished account to gather more passwords.

"Coming from a trusted address, many staff members clicked the link, but most refrained from entering their login credentials," The Onion post explains. "Two staff members did enter their credentials, one of whom had access to all of our social media accounts."

The Onion sent a company-wide message asking employees to change email passwords immediately but the hacker used another compromised account to re-send the phishing URL, this time disguised as a password reset link within the company's warning email.

Earlier this week Twitter introduced two-step security, requiring users to enter an extra password sent to their mobile phone. As a post on GigaOm states, "two-factor authentication would likely have prevented those attacks because the attackers would have had to enter a password sent to the employee’s cell phone".

So what advice should journalists follow? We spoke to Daniel Cuthbert, chief operating officer at information security firm Sensepost.

Awareness is crucial, Cuthbert told Journalism.co.uk. "It's not about if you are going to get attacked, it is about when you get attacked. That's the nature of the internet today and people are trying that all the time."

1. Choose a strong password

Choose a strong alphanumeric password that is a combination of uppercase and lowercase letters and numbers. You can use a password generator such as this one.

"When you see people saying 'my Twitter has been hacked', most of the time it is because they have chosen a really weak password, and the attacker is just an opportunist attacker," Cuthbert said. "They have gone through and tried various passwords. A strong password stops the opportunists trying things like 'password12'," Cuthbert said.

People often create passwords related to things they are interested in, whether pets or family members or football teams. A hacker might go though your Facebook account (if it is visible to everyone) and be able to guess a password from that information.

You may have based your Twitter password on an interest as it is easier to enter when on a mobile phone than a combination of lowercase and uppercase letters, or because it is simply easier to remember. There is a temptation to write down alphanumeric passwords whether in a document on your computer or on post-it note or in a diary, something Cuthbert strongly advises against.

So what is the solution? A tool Cuthbert uses personally is called 1Password. "It's a fantastic tool," he said (explaining that he was not trying to plug it). "The nice thing is that it works with your browser so you can set a random password that is 40 characters long. You never have to see that password but you can just put it into the web pages your are browsing. It forces you to think more about password security."

2. Set up two-step security

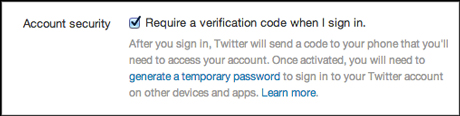

On Wednesday (22 May) Twitter announced that it had introduced two-step security, and created a one-minute video to show people how to activate it.

"Now that Twitter has finally introduced two-factor authentication, turn it on," Cuthbert advises. "Go into your Twitter settings, go down to your account page and under 'account security' click the button which says 'require a verification code when I sign in'."

This provides "another layer", he said, and "is going to stop the attacker having free rein by putting a few road blocks in their way".

3. Don't click on suspicious links

As explained above, news outlets have had their Twitter accounts hacked due to a member of staff with access to passwords clicking on a malicious link.

These attacks were targeted at key individuals. "The attackers did their homework," Cuthbert said. "They figured out who the person was in the organisation, how much control they had over the organisation's Twitter account, and they crafted a fairly advanced attack aimed at that person."

In the case of The Onion the phishing link was in an email. This is often effective as "if you are a journalist you are used to receiving emails from people with leads to stories or documents", Cuthbert said.

And from the first email the hacker "will either try and exploit a trust relationship within an organisation", such as was the case outlined above with the hacked staff member's Gmail being used to send a further message to colleagues.

"If I was going after a journalist I would probably go down this approach too," security expert Cuthbert said. "I would create a malicious document, be it a PDF or Word or Excel, and have some content in there so I get you hooked. I would then use this to take control of your machine."

"All the attacker needs is that one single click," Cuthbert warned, and it is relatively easy for the hacker to do this. "The information is out there, the tools are very easy to use these days so it's not like it requires a high level of intelligence like it did a decade ago."

Once the hacker has gained access to that machine, it is very easy for him or her "to gain access to all the sites you have access too".

Cuthbert demonstrated this at last Tuesday's Hacks/Hackers London, a meetup of technologists and journalists, showing how the hackers can activate the video camera within your computer and record every keystroke you make.

That hacker can then "re-set your password, see what new passwords you are setting just by sitting there listening for a couple of weeks", Cuthbert said. "You would be completely unaware that you were being watched."

"If you are not ultra paranoid, it is very hard for you to know if someone has gained control of your machine and is busy looking at what you are doing. There are techniques to turn off the green light [which denotes the camera being on], there are techniques to hide your tracks. The odds are really against you if you are trying to work out if you have been attached."

One tip is to install a tool such as Little Snitch for Mac. "Little Snitch is an amazing tool," Cuthbert said. "It tells you who is doing what and who is connecting where and when."

4. Limit who has access to the brand's Twitter account

The advice for those responsible for a brand's Twitter account is to limit who has access. "If you are a big news organisation with a lot of followers, you have sort of a moral responsibility to ensure you are taking enough security measures so that people are not misled," Cuthbert said.

If you are a follower of that account, you probably expect that company to be fairly good with security, he added.

Additional advice

The Onion post has additional advice. "The email addresses for your Twitter accounts should be on a system that is isolated from your organisation’s normal email," the post states.

It also advises pushing all Twitter activity through an app such as HootSuite.

The post suggests finding a way of contacting staff outside of their work email address. "If possible, have a way to reach out to all of your users outside of their organisational email," it says, explaining that in the case of the Guardian hack, the Syrian Electronic Army "posted screenshots of multiple internal security emails, probably from a compromised email address that was overlooked".

Other security advice

So what other security advice should journalists follow? Cuthbert said it is important to keep your computer updated, particularly the plugins. "So when you see that Adobe Flash update, when you see there is a Java update, update them. "A lot of these attacks are unknown to Java at the time, but just keep your machine updated and be aware."

He also warns that wifi "should be untrusted". At this week's Hacks/Hackers event he brought along a Snoopy device, which looks much like a mobile phone but is able to track and profile any mobile phone connected to a wifi network.

"Wifi is a dirty network," Cuthbert said, "so be careful what you are doing".

"So when you are sitting in a coffee shop, there could be someone like me sitting with a Snoopy drone looking at the traffic. It is a very old technique, but it is still incredibly effective."

Northern Ireland-based investigative journalist Lyra McKee has also written on internet security for journalists. Her article is on the Online Journalism Blog.

(Disclaimer: Sarah Marshall is one of the organisers of the Hacks/Hackers London meetups)

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).