Fresh research by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) reveals that a growing portion of the UK population is at risk of being uninformed or misinformed about the coronavirus pandemic.

Other recent and international surveys have shown that journalists think trust between themselves and audiences have increased during covid-19. However, the new study by RISJ, Communications in the coronavirus crisis: lessons for the second wave, suggests that trust in the UK media is, in fact, falling when it comes to covid-19 news.

RISJ completed the ten-wave survey between April and August in two-week intervals. The number of respondents per wave descended from 2,823 to 1,003 between the start and the finish, as it endeavoured to survey the same people throughout.

The data shows that trust in news organisations as a source of information about the pandemic fell 12 percentage points from 57 per cent in April to 45 per cent in August. Daily news use also dropped 24 points over the same period, from 79 per cent to 55 per cent.

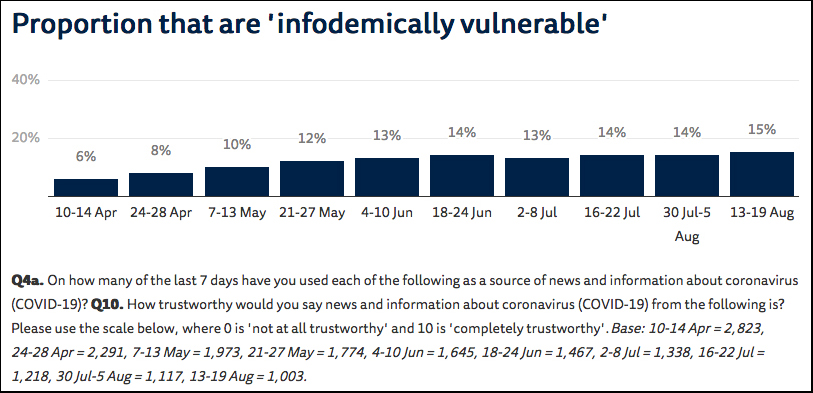

What this decline points to is an emergence of the 'infodemically vulnerable'. This is a group of people who consume little to no news and information about covid-19 and do not trust it even if it reaches them.

This group has grown from 6 per cent of the population early in the crisis to 15 per cent by late August. Extrapolated to the UK population, this equates to around 8 million people. This group is skewed towards younger audiences with lower levels of formal education.

"The combination of not paying attention to the news and being sceptical or actively distrustful leaves people more at risk at best of being less informed and at worst of being uninformed or even worse, misinformed," says Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, director of RISJ and lead author of the study.

When confidence in the government dwindles, trust in the media follows suit, he added. Though it is not a 'one to one' relationship, part of this dynamic of mistrust and scepticism towards the media is down to who features in the news.

RISJ studies published in June showed that public trust in the UK government fell from 67 per cent to 48 per cent in a six-week period during April and May. This decline was seen across the political spectrum, and by extension, news organisations.

"This is extremely challenging from the point of view of editors and journalists. You have very good reasons for wanting to cover the government, the opposition and other voices, and what they say and do about the crisis," Nielsen adds.

"The challenge is that many people hold these politicians in very low esteem and this attention can come across as being at the expense of addressing the questions people have.

"These questions are much more practical and less about 'What does this MP, mayor or minister think, say and criticise?' They'd much rather know what they can do, which usual coverage rarely addresses."

Millions of people remain unsure of what rules and laws apply to them regarding the pandemic. Just 61 per cent of people think the news media have explained what the public can do in response to covid-19, faring better than the government at 58 per cent on the same criteria.

Despite that, most people are well-informed. Three quarters of respondents answered correctly to more than five out of eight factual questions about covid-19. Respondents who gave incorrect answers erred on the side of caution: for example, a quarter correctly answered how long to stay at home for if they are showing covid-19 symptoms (10 days). 70 cent of respondents answered 14-21 days.

Coronavirus jargon was also a large unknown in February but most people now understand what some medical terms mean, including 'antibody test' (77 per cent) and 'the R number' (86 per cent).

The big question remains how to reach audiences who fundamentally do not want to be reached. How can we stop this decline of audience trust? A start would be straying away from interviewing Westminster elites and rethinking audiences' access to the news.

"Crudely put: more nurses and doctors and fewer politicians and pundits might be a sensible approach for editors who want to feature sources that people trust, rather than sources people are very sceptical about," Nielsen says.

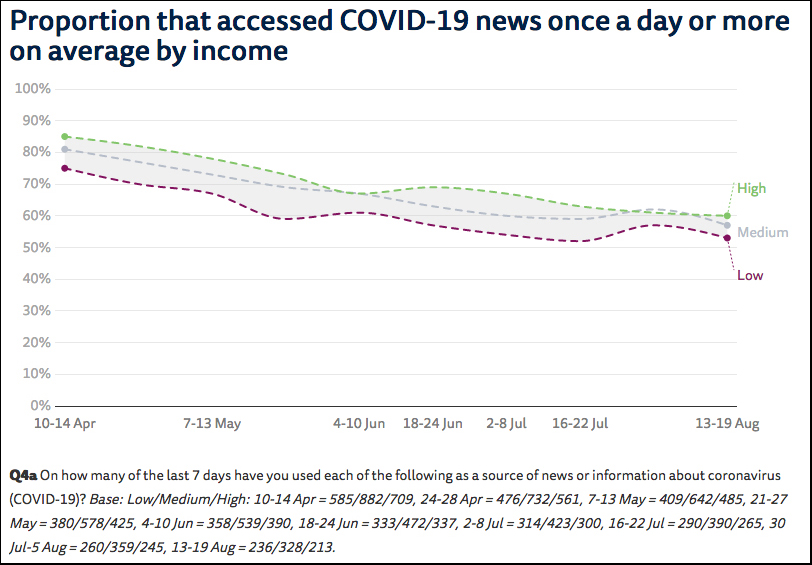

"Also there is a structural challenge that an increasing number of news organisations are basing their business on reaching people who are willing to pay for the news and these are overwhelmingly news lovers, more affluent, highly educated and privileged."

He added that there is a greater responsibility to address information inequality for the public broadcaster BBC that has a duty to serve parts of the public that the commercial media are not successfully reaching.

The UK has had a crisis of trust for years now. It was felt in many recent news events, like debates around Brexit and the UK general election debate. The prospect of a second coronavirus wave is perhaps a chance to rectify a longstanding industry problem.

Although there is no overnight solution for public trust towards the media, Nielsen said the next phase of the coronavirus pandemic will be a "defining moment". It is an opportunity to re-conceptualise who they want to appeal to and examine how to win the trust of a sceptical public.

"Many people are not that interested in politics and not willing to pay for the news. The road back into their affection is not one focused on what elected officials are arguing about today and more about showing that the news makes peoples lives better in some very concrete and actionable way."

Calling all Telegram users: join our journalism news channel to receive an audio update every Monday morning, and our journalism jobs channel to find out the latest opportunities

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).

Related articles

- How do journalists really want to use generative AI?

- What AI can do for your newsroom: tips from Ring Publishing's latest handbook

- What can news organisations do to win over consistent news avoiders?

- Creating and developing GenAI workflows in the newsroom, with David Caswell

- Ukrainian journalists are at a breaking point. It is time to make a change