In a world turned upside down by the coronavirus pandemic, it is strangely comforting to see the annual Reuters Institute Digital News Report being released today (16 June 2020).

Although the research team, led by Nic Newman, had started collecting data for this study before the covid-19 crisis hit, they have done additional research to offer a complete picture of how the pandemic has affected the news industry.

Unsurprisingly, lockdown has impacted news habits across all 40 surveyed countries. In the UK, notably, TV news consumption has increased between January and April 2020 across all age groups, with the highest increase in the under-35s (25 percentage points). The online news outlets have also seen an uptick in the traffic.

One of the biggest surprises has been the rise of less-obvious social media as the main source of news amongst the 18-24s. In the UK, nearly a quarter (24 per cent) of younger audiences are getting their news on Instagram, while almost one-fifth (19 per cent) go to Snapchat.

It is too early to tell just how much the covid-19 crisis has impacted the news sector. The traffic boost has been real, said Newman, but the biggest impact of coronavirus on the media is going to be economic.

While some publishers have seen a rise in paying subscribers, many have reported their advertising revenue has fallen by a half. Some print newspapers had to stop their physical editions and lay off staff.

Courtesy RISJ

All of this puts pressure on the media to rethink their business model. We are likely to see the rise of reader-revenue model as the number of people paying for online news has increased significantly during the pandemic across surveyed countries.

While this is good news for newsroom revenue, many worry about growing levels of information inequality. Those with less money will have to rely on low-quality news and social media, while the more fortunate will be able to afford premium information.

In the US, nearly one in four (24 per cent) people are concerned about information inequality, while fewer than one in ten (9 per cent) worry about it in the UK. The authors of the report propose that lower levels of concern in the UK may be due to availability of quality public service news from BBC but also other popular titles, such as the Guardian with its open donation model.

Why do readers subscribe?

Whether local or national, people are more likely to pay for news when they feel they are getting a distinctive product and good value. However, they are also willing to support journalism especially when it is perceived as being under attack.

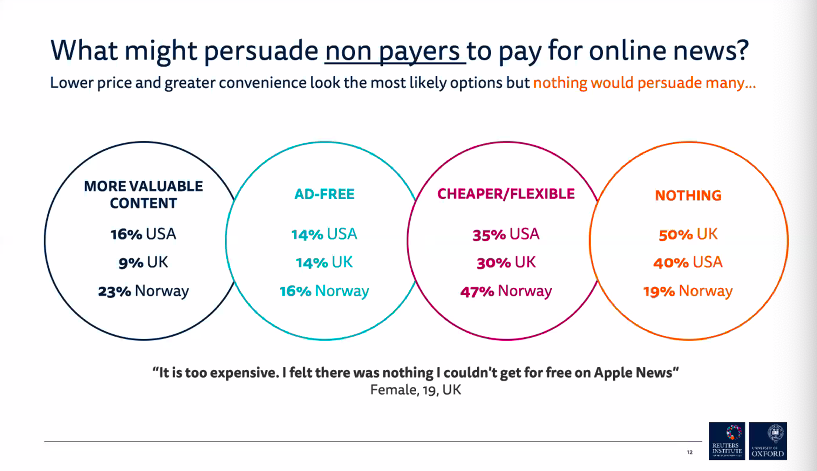

Some are also persuaded to pay to get ad-free content but in counties like the UK, half of the audience is not willing to pay for news at all.

Courtesy RISJ

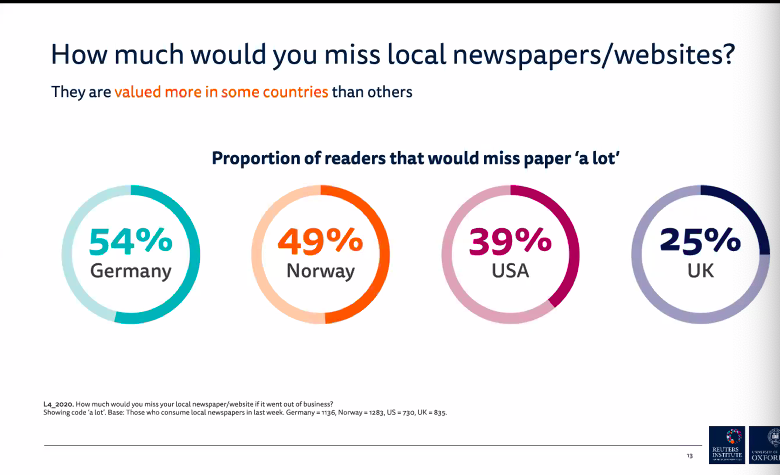

The UK picture is even bleaker when it comes to local news - three-quarters of respondents who regularly read local newspapers and websites said they would not miss them at all if they disappeared.

Courtesy RISJ

Trust in news and misinformation

When the pandemic hit, RISJ recorded the lowest levels of trust in the news since it started to track this data. Fewer than four in ten (38 per cent) people said they trust most news most of the time, and less than half (46 per cent) trust the news sources they use themselves.

One of the common denominators among the countries with low trust in the news seems to be the growing divisions society. This is true not only in the UK, where trust in news fell by 12 points since last year, but also in Hong Kong where street protests are ongoing, or in Chile after months of demonstrations against inequality.

Political allegiance also seems to play a role in how much people trust the media. In the UK, for instance, left-leaning audiences said they trust the news less (15 per cent) than the right-leaning ones (36 per cent), after the sweeping victory of the Conservative Party in 2019 and the perceived unfair media treatment of the Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn.

The study showed a similar trend in the US but in reverse. Those who self-identify as right-leaning have lost trust in the media (only 13 per cent said they trust the news) after years of anti-media rhetoric by President Trump. For those on the left, the trust in the news continues to fall, although 39 per cent still trust most news most of the time.

When it comes to misinformation, people see domestic politicians as most responsible (40 per cent) for misleading news online, while 13 per cent are concerned about misinformation from journalists and 10 per cent worry about lies from foreign governments.

In the most polarised countries, like the UK and the US, political leaning once again weighs in. Right-wing supporters of Boris Johnson and Donald Trump are far more likely to blame journalists for misinformation, while their left-leaning opponents are more inclined to blame these politicians.

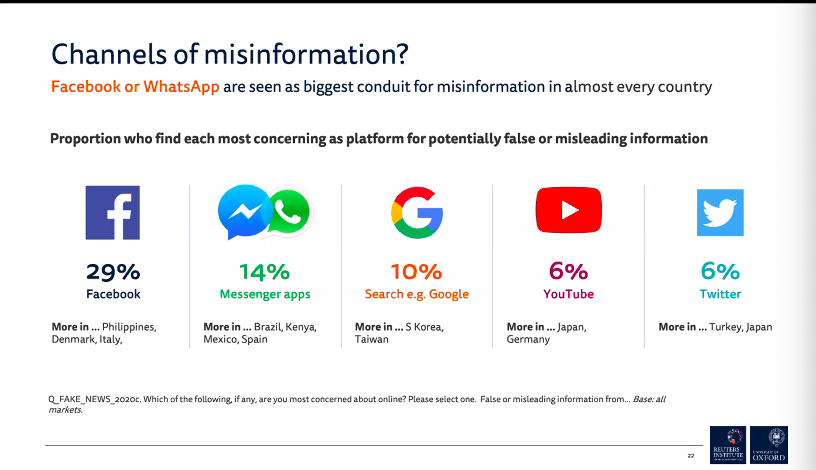

The choice of news sources also matters when it comes to misinformation. Four in ten respondents consider social media as the main source of misinformation, while only two in ten are concerned about misleading information on news sites.

Drilling deeper into the data, Facebook is the most mistrusted source (29 per cent) of news when it comes to accuracy, followed by YouTube (6 per cent) and Twitter (5 per cent). However, people in countries like Brazil or Singapore are more concerned about closed messaging apps like WhatsApp (35 per cent).

Courtesy RISJ

Resurgence of editorial curation?

As publishers have to increasingly compete with platforms, they are trying to build a direct relationship with their audiences through email, mobile alerts and podcasts.

Across all surveyed countries, 16 per cent of people get information from newsletters, (21 per cent in the US but only 9 per cent in the UK). Curation is becoming an increasingly important part of newsroom work - New York Times, for instance, offers almost 70 different email products and its morning briefing has now 17 million subscribers.

Podcasts are also faring well. After a reported drop in podcast listening during the lockdown, that many attributed to nearly non-existing commuting, RISJ data show a rebound. Across 20 tracked countries, 31 per cent of audiences tune into a podcast (44 per cent in Spain but only 22 per cent in the UK). News and politics shows are among the most popular.

Given that podcast listener tend to be younger - in the UK, half of all podcasts are listened to by under-35s - this could be a great opportunity for broadcasters who struggle to reach this demographic.

Join Journalism.co.uk at our virtual Newsrewired conference for the latest expert insights on newsroom revenue and innovation during the pandemic. Click here for more information.

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).

Related articles

- Journalists are happy to be disconnecting from platforms, should news organisations be worried?

- Protecting journalists on social media, with Valérie Bélair-Gagnon

- What will your audience want in the future?

- New resources to help journalists fight elections misinformation

- 15 free sources of data on the media industry