Back in October 2015, Juan Torres, innovation editor at Brazilian news outlet Correio, boarded a two-hour flight from Salvador to visit his family in Rio de Janeiro.

Right before he left, a big storm had hit the city, so when he landed in Rio, he quickly turned on his mobile to check the weather updates on Correio's website.

But, Torres said, he quickly realised the site might not be the best source for the information he needed, so instead he asked about it in the WhatsApp group he shared with his circle of friends.

"Twenty minutes before I had even asked, one of my friends had shared a video of the rain and the flood, so I had the information I wanted without having to give any input," Torres told Journalism.co.uk.

We wanted to test this hypothesis that maybe the media doesn't need to be the holder of the information anymoreJuan Torres, Correio

"And I started thinking about how useful [Correio] could be if we started gathering people around their interests, whether that's news about the city, economics or sports, and maybe even have our desks producing for WhatsApp groups."

At the time, WhatsApp's group chat feature was limited to only 100 people. But that increased to 256 at the beginning of February, so Torres decided to start experimenting with Correio's audience on the platform, as the 37 year-old newspaper has recently been trying to improve its digital presence.

"We wanted to test this hypothesis that maybe the media doesn't need to be the holder of the information anymore.

"So we put ourselves in the position of bringing these people together, but without being at the centre of the information exchange," Torres said.

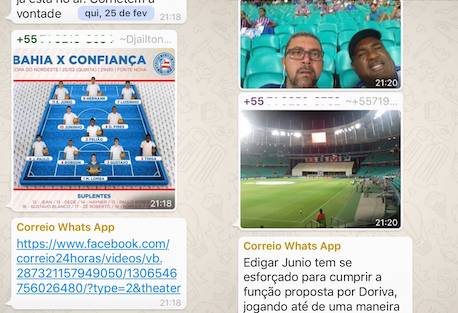

Two days before a football match on 26 February between the state's team Bahia and another Brazilian team called Ad Confiança, Correio published a Google form enabling people to sign up to join the outlet's new WhatsApp group, promoting it on its website and social media accounts.

Readers had to provide their name, email, phone number, the neighbourhood they lived in and the football team they supported. The first 59 people to fill in the form were added to the group within the first 30 minutes. In 24 hours, Correio had 253 sign-up requests in the Google form, but the experiment was limited to the first batch of users.

"We operated the WhatsApp group for two hours, while the game lasted, and we chose that number of people [59] because that was the year the Bahia team had won the national cup.

"At first our concern was that because we chose football, a topic people are so passionate about, the language in the group might be an issue or that the match would cause arguments, but we didn't have that at all."

The team set only two rules, telling participants they would be kicked out of the WhatsApp group if they misbehaved or if they promoted products or companies.

During the game, Torres's work resumed to sharing a few game analysis articles from Correio and some short videos one of their reporters at the stadium had shot for Facebook and Instagram.

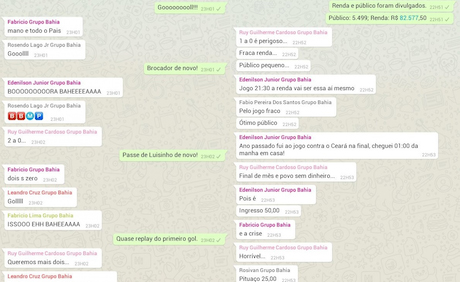

Members of the group kept the conversation going by publishing information about the football players, the number of attendees at the match and posting game updates from social media.

Correio staff left the group after the match, something they had stated from the beginning of the experiment, but they found out the group remained active, with users changing its name to Correio Bahia.

"People saw a lot of value in gathering around such an important issue for them, and they told us they hoped we would do the experiment again."

Correio is not the first news outlet to experiment with the messaging app for live events coverage.

In December, the Guardian's Mobile Innovation Lab used a WhatsApp broadcast list to start a dialogue between their audience and one of the organisation's culture and politics reporters around the Republican presidential debate in the US.

The app's broadcast lists are also limited to 256 members, but they work a little differently. Members are treated more like subscribers to a newsfeed, where only the host can send out updates. They can reply to the journalist individually, but they can't chat to each other within the list.

The problem with using a broadcast list is the lack of interactivity. You still put yourself in charge of the information, whereas in a group, you are part of the communityJuan Torres, Correio

Torres said Correio was aware of the Guardian's experiment before they conducted their own, but decided to use groups instead of broadcast lists because it allowed for more interaction between the reporters and the community, as well as the participants themselves.

"Their approach gave us some great insights, especially into putting ourselves out there less institutionally and more like human beings," he explained.

"But the problem with using a broadcast list is the lack of interactivity. You still put yourself in charge of the information, whereas in a group, you are part of the community."

The next step for Correio is finding a way to monetise the initiative, talking to commercial partners such as the football stadium and local football clubs about the possibility of placing ads within the group.

"If it's really valuable, maybe people would even pay to be in a group like this," Torres said.

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).

Related articles

- 15 year old local publisher launching in print

- Noon founder Eleanor Mills: "Women don't have a sell-by date"

- How The New Humanitarian covered the Lebanese economic collapse using WhatsApp

- Tip: Community advisory boards 101

- Sky News and BuzzFeed UK collaborate on livestreaming UK general election 2019 overnight show