Not every news story is a clear-cut case of who said what; more often than not newsworthy events raise more questions than answers.

But in the age of social media, many news organisations are not doing enough to quash mistruths in the early hours of a breaking story – and may even be helping lies spread – according to a new report published yesterday by the Tow Center.

In "Lies, Damn Lies, And Viral Content", report author and Tow fellow Craig Silverman argues that some news organisations are inadvertently propagating lies or rumours from social media in an effort to get more clicks and shares.

"There are a lot of very large news websites whose strategy is 'anything out there we want represented on our site'," Silverman told Journalism.co.uk, "and as long as that strategy is there and bearing fruit for at least some sites, then you're going to have [unverified] things getting out there."

Rumours can be valuable in terms of understanding the wider context of a story and how it is perceived in a process of "shared sense-making", he said, but many sites reference other news organisations as a source in an effort to "cover the thing without having to take the responsibility".The attractive lie is far more shareable and interesting than the often more complicated truth.Craig Silverman, Tow Center fellow

"If you diagrammed what's going on, you would have one piece of content that's out there that one news site will write about," he said, "and from there you have this never-ending cycle of inter-linked articles all pointing back to each other.

"There's not a lot of verification going on, there's not a lot of reporting going on, it's just hit and run."

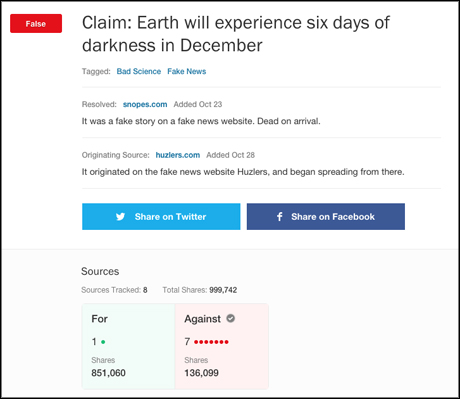

Unverified stories were logged on Silverman's real-time rumour tracking site Emergent.info as 'claims', then followed to see which news sites would report a claim, what language they used and what action was taken once a claim was verified as true or false.

News organisations fell largely into two camps, said Silverman, the "mindless propagators" and those who exercise "silent restraint", not sharing any information that they cannot be sure about.

"There's got to be some kind of middle ground where we're helping people understand the context and the factual nature of what's out there," Silverman said.

However, the language of reporting falsehoods or unverified claims can be a minefield of misinformation.

Psychological and sociological studies have shown that, with headlines posited as a question, the reader's brain often processes the initial statement as true before processing the question mark, said Silverman.

When it comes to headlines that follow the now meme-like "questions to which the answer is no" (#QTWTAIN) format, this can have the undesired effect of leaving readers misinformed.

"The attractive lie is far more shareable and interesting than the often more complicated truth," Silverman said. "You have a harder base of material to work from when you're trying to disprove something, rather than make a claim about something that generates emotion or some other type of reactions from people."

A blatant mistruth that nonetheless received four times as many shares as articles debunking it. Screenshot from Emergent.info

"There's no A/B testing going on of debunking headlines," he continued, "whereas people are A/B testing the viral headlines all the time.

"So hopefully folks look at this the way I look at it and think if we actually applied some resources to this, this is a whole new type of content that has the potential to be viral and it also fulfils the basic mission of journalism as opposed to having us spread a bunch of misinformation."

The full report is available to read and download for free from the Tow Center.

Related articles:

How to deal with online rumours and debunking responsibly

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).

Related articles

- Six self-care tips for journalists to stay sane during the US election

- Blockchain can help news publishers fight risks posed by fake news websites

- RISJ Digital News Report 2024: Three essential points for your newsroom

- Seven tips for using LinkedIn as a freelance journalist

- Journalists are happy to be disconnecting from platforms, should news organisations be worried?