The old adage says that a 'picture tells a thousand words'. And by using just two satellite images from Google Earth, taken two months apart, a citizen journalist has been able to tell the story of the end of Sri Lanka's 25-year civil war.

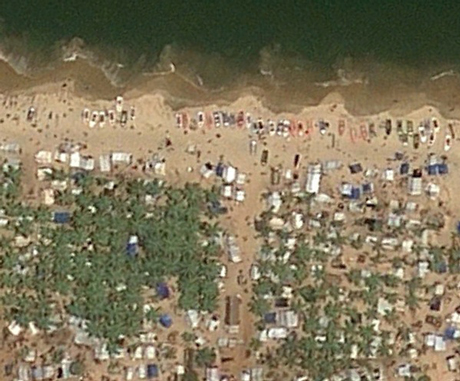

Back in November 2012, Sanjana Hattotuwa, founding editor of Groundviews, a site dedicated to 'journalism for citizens', realised that by using the Google Earth time slider, a tool which shows satellite imagery taken on different dates, he could see the presence and subsequent disappearance of refugee camps. The images show a littoral sliver of land between the sea and a lagoon in the north-east of Sri Lanka where displaced people were living in camps.

An image taken in March 2009, two months before the end of the war, shows the refugee camps; by May 2009 Google Earth documents the area as a "barren wasteland", as Hattotuwa explains in this post.

"It is one thing to read about what happened in that area in the first five months of 2009, through what we can find on Human Rights Watch or Amnesty International," Hattotuwa told Journalism.co.uk. "It is quite another thing to see what was the reality on the ground.

"Even seeing it on Google Earth is chilling, it is horrific. You are talking about hundreds of thousands of people in a sliver of land living in unimaginable horror," he said, something that will be familiar to anyone who has watched Channel 4's award-winning documentary on Sri Lanka's civil war.

In an interview with Journalism.co.uk at the World Editors Forum, held in Bangkok last week, Hattotuwa, who was a speaker at the conference, said when he used the timeline slider on Google Earth he "was astounded to realise that there are four occasions where the war ending is catalogued". (The audio interview with Hattotuwa is here.)

"The intention was not actually to ascertain culpability," Hattotuwa said in the interview. "It is impossible to ascertain who shot what and when, but it is very clear from the imagery that it's a scorched earth policy, you can see pock marks all over the place."

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google EarthHattotuwa addded: "It is an interesting use case of Google Earth to flesh out inconvenient truths about a country's recent past."

A second post on Groundviews uses Google Earth to show what Hattotuwa identifies as mass graves, which he explains were highlighted in a report by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. In the article Hattotuwa explains how he used a Mac programme called Kaleidoscope to carry out image difference analysis.

Referring to both Google Earth case studies Hattotuwa said "there is no other archive of the story".

It is an interesting use case of Google Earth to flesh out inconvenient truths about a country's recent pastSanjana Hattotuwa

"There's no other archive at all, anywhere in the world. And it is also impossible to create another archive as the geo-spacial imagery is so large, you can't exactly download it from Google Earth."

He also raised concern that the unique archive of data is owned by Google.

"Imagery that is vital to my country's historical narrative is resident only on Google and is completely hostage to Google's policies on corporate data retention," Hattotuwa said. "It is a wonderful archive to have but I am very fearful that for the future generations it might not be there."

Creating a Twitter archive

And Hattotuwa, who describes himself as an activist as well as a citizen journalist, says there is a recent history of Sri Lanka on Twitter that needs archiving.

"We produce information on Twitter, but as a platform it is ephemeral in that what you produce today is incredibly difficult to find, even a week down the line," he said.

He used the example of tweets sent in the aftermath of the 2010 Haiti earthquake. The messages posted on Twitter "are almost impossible to access today", he said.

"If you were not to archive this you would be, in a sense, losing out on country's history. It is important for me as an activist but also as someone who is interested in the multiple stories around the country to archive it."

Hattotuwa has archived a number Twitter discussions, based on hashtags or Twitter accounts (here is one example). He uses a tool called Twitter Archiving Google Spreadsheets, or TAGS, (which was created by Martin Hawksey).

"The tool has two components: it becomes a searchable archive of all the tweets around the period you capture them, but it also is a superb data visualisation tool as well, so you can visually drill down into who said what, in response to whom, why and when," Hattotuwa explained.

A view from the ground

Speaking at the World Editors Forum, Hattotuwa explained how Groundviews, which he founded in 2006, operates in "a country that is not known for its tolerance, or its independence and critical perspectives".

Sri Lanka is in position 162 out of 179 in the 2013 Press Freedom Index.

"You can imagine how difficult it is, how frustrating it is, to report on some of the stories that matter" Hattotuwa told Journalism.co.uk. "It is easier for me to do it as a lone voice with no newsroom to think about, no advertising to be concerned about."

In addition to storytelling with Google Earth and TAGS, Groundworks is using a range of free tools.

"It’s the stories for us that matter," Hattotuwa said. "These stories that need telling, retelling and archiving as they aren’t being told."

For those interested in Sri Lanka, here is a comment piece from Frances Harrison, a former BBC correspondent in Sri Lanka: 'Journalists failed to tell the story of war crimes in Sri Lanka'. Harrison is author of 'Still Counting the Dead'.

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).

Related articles

- Updated global directory features 3,000 independent digital media companies

- Nine AI tools for journalists to try this summer

- Tool for journalists: Story SpinnerAI, for generating story angles based on user needs

- Why TikTok star Sophia Smith Galer created an AI tool to help journalists make viral videos

- Audiences, sources and strategies: Inside The New Humanitarian's Yemen Listening Project