"There is no such thing as 'the news' in the way it was 50 years ago", believes David Dunkley Gyimah, an award-winning video journalist and a lecturer at the University of Westminster.

Speaking at the International Journalism Festival in Perugia, he noted that though much has changed in the news industry, the format and methodology for video reportage has not.

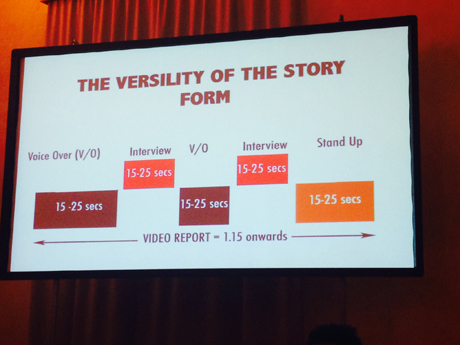

For video and broadcast journalism, especially for news, the standard 'package' has remained the same since the 1950s, he said. On the other hand, the way journalists produce and distribute the written word has changed more than anyone could have envisaged.

Standard package of a broadcasted news story

How people "understand 21st century video storytelling" needs some serious revisions, Dunkley Gyimah pointed out, for a number of reasons.

One of the most prominent changes to the video landscape was the advent of YouTube in 2005, allowing anyone with an internet connection to create and distribute video content – the most significant event in what Dunkley Gyimah described as a "landmark year".

Being so publicly accesible, YouTube has allowed a greater variety of styles and influences to come to the fore, which audiences have reacted positively to, he said. So where does that leave news?

The 'package' is a traditional way to tell a story – but it need not be the only, or always the best, way. Dunkley Gyimah played delegates two versions of the same story – the devastated town of Beichuan in China, where mourners still return to look for the bodies of their family members killed in an earthquake.

In Beichuan, the Agony of Surviving from Travis Fox on Vimeo.

Though the fact that people still return to look for their family is tragic, because the earthquake happened in 2008 it is no longer seen as news. Instead, it is a human interest story that can be told through a different lens to give it more emotional impact, Dunkley Gyimah said, and to put the viewer into the story. Here, a more 'cinematic' style may be appropriate, he said.

But rather than the Hollywood interpretation of 'cinematic', Dunkley Gyimah insisted video journalism could adopt cinema's original meaning of "detecting a plot from a scenario" – recording events on the ground and reacting to them, rather than going in with a set idea and shooting footage to fit.

An artistic background can help video-journalists have a "broader palette" with which to shoot truly cinematic footage, which can then tell stories in a fuller, more affecting manner, he said.It comes from discussions, in the same way as coders and journalists came togetherDavid Dunkley Gyimah, University of Westminster

However, this does not mean the role of the reporter, or correspondent, is dead.

Some of the best video reporters know how to "let the story breathe," Dunkley Gyimah told Journalism.co.uk. One example is the Travis Fox story on Beichuan.

"[Fox's] voice comes in at 21 seconds. Twenty-one seconds of sheer emotion, which isn't gratuitous, he's building it up, letting you into the film and in 21 seconds comes and gives you the voice over and context."

For breaking news and evolving stories it may be clearer to tell the story straight, but when there is enough background information to contextualise events both the journalist and filmmaker can take a different approach.

Vice have traditionally called themselves 'filmmakers' rather than broadcasters or news, and Dunkley Gyimah sees the collaboration with the more artistic elements of the industry as an area for exploration, in the similar way to other collaborations.

In another example, filmmaker Marwaan Maalouf, speaking alongside Dunkley Gyimah, showed clips from his film False Alarm, which tells the story of the Syrian conflict through the eyes of 15 video journalists on the ground.

"It isn't a defined science, it comes from discussions," he said, "in the same way as coders and journalists came together and they started to learn from each other and this marriage has suited them well in data journalism."The audience is saying to us 'we like films and can tell the difference between cinema fact and cinema fiction'David Dunkley Gyimah, University of Westminster

The same could be true in telling powerful news stories that the audience wants to engage with in a more contemporary manner than the outdated 'package' format.

"The audience is saying to us 'we like films and can tell the difference between cinema fact and cinema fiction'," he said.

Ethical questions may arise if stories are twisted for purposes of "propaganda", but 'cinema journalism' is just one alternative to current ideas of video news, rather than a definitive alternative, Dunkley Gyimah said.

He added that the blurred lines between who is and is not a journalist, and what is or is not a news report, should be a cause for experimentation and collaboration.

"The constraints [on the styles] are different. Where that boundary used to exist – 2005 took them away.

"You could argue that without the internet there wouldn't be a Vice."

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).

Related articles

- Livestreaming, explainer videos and newsletters: Overnight election coverage with three new media companies

- Why video journalism is not ready to ditch its editors

- Video meets podcast: Five tips for making a successful 'vodcast'

- Newsrooms must step up their efforts to cover gender equality stories

- New project InOldNews wants to improve representation in video journalism