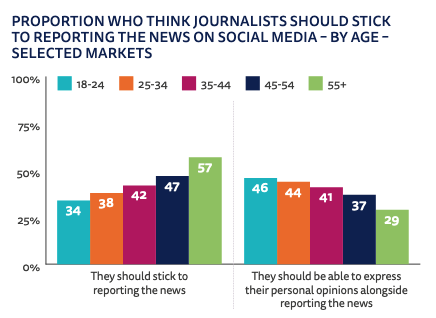

In the recently released Reuters Digital News Report 2022, one key finding centered on how younger and older news consumers believe journalists should behave on social media: "In our survey, around half of respondents or more in most countries feel that journalists should stick to reporting the news, but a sizeable minority believed they should be allowed to express their personal opinions on social media at the same time."

It appears to be mostly a generational gap. "As some media organisations tighten social media guidelines, they are facing resistance from younger journalists who take a different view, and are trying to push the boundaries. This is just another way in which journalistic norms are being challenged by social and digital media."

As I have written elsewhere, "Within journalism, there is a reckoning over 'objectivity' and internal struggle sessions to replace it. Most notably in the wake of the George Floyd murder, Wesley Lowery has called to replace objectivity with moral clarity.'"

In The New York Times, Pulitzer-winning CBS journalist Lowery makes a compelling case that news organisations, which have historically been rooted in objectivity, should wear their decisions on their sleeves and take sides.

There is much to laud in this view, often championed by a younger generation of journalists. But it is also worth thinking critically about the framing of "objectivity" in this conversation.

Are these critiques really against "objectivity" or a kind of moral equivalency? "He said, she said" reporting is not the same as "remaining objective." Nor does objectivity preclude somebody from having their own sense of truth.

What do we mean by "objective"?

To gain some clarity, let's bring the sciences into the mix, a field where most still agree "objectivity" is an integral value for any meaningful work to get done. Despite this goal, I think it is fair to say scientists (the individuals) are not objective.

A common retort within journalism is that nobody is neutral and therefore nothing they produce can be objective. Scientists are humans too and they are not neutral either. Every decision a scientist makes is steeped in their point of view. The question of "what should we study" itself takes away impartiality.

The scientific process, which they follow, however, is a routine meant to ensure their work remains objective. It is the process, not the person, where objectivity becomes an emergent property.

Once the experiment is over, the real refinement begins. A science experiment is only meaningful if other scientists can replicate the findings. Without this peer-review method, science is meaningless.

One could argue the very definition of a scientific finding is that it can be replicated despite the human flaws of the individual scientist and their personal truths or philosophies: the same could be said of journalism.

A distinction: Truth vs. fact

Another important distinction to make is between "truth" and "fact." I have long argued that journalists need to better understand this distinction and acknowledge that we have a foot in both domains. In philosophy, this is known as the fact-value distinction.

A movie review, for example, can include facts, like who directed the film, quotes, still-images from the movie and even a summary of the plotline. But a thumbs-up/down rating is ultimately in the realm of truth.

And while it seems trivial, let's imagine a politically significant movie where the thumbs up/down rating is also seen as a moral judgment. In this scenario, would we deny the movie reviewer the ability to post their thoughts on social media? Of course not. Similarly, we would expect the movie reviewer to keep facts "objective" or repeatable. In fact, to get these wrong would discredit their moral pronouncement that the film was good or bad.

In short, moral clarity and objectivity are not mutually exclusive.

The Reuters report suggests that younger readers value authenticity (particularly shown on social media) from reporters whereas older readers put a premium on old-school objectivity - and while this reads as a tension, I believe most of our audience leaves wiggle room for both.

In authenticity we trust?

Of course, all of this has a downstream effect on trust. The report finds that this year audiences had lower levels of overall trust in 21 of 46 markets. Trust in my country, the US, stands at 26 per cent, representing a three percentage point drop from last year and maintains its position with the lowest levels of trust in the survey.

Adjudicating between truth and objectivity is not easy. I understand the appeal of and move towards a more authentic journalist who does not hide their sense of truth and rejects political neutrality. I also understand the scientist who speaks out with their political views.

In both cases, there is room to remain objective and maintain a process of reporting, repeatability, checks and facts. Indeed, doing so does not take away from one's own perspective, it can bolster it further.

David Cohn is the co-founder and chief strategy officer of Subtext, and senior director of Advance Digital, where he leads the 'Alpha Group,' an internal research and development team. He spent seven years as a freelance journalist, writing for titles including Wired, The New York Times, Seed Magazine, Quartz and Columbia Journalism Review.

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).

Related articles

- RISJ Digital News Report 2024: User needs with Vogue and The Conversation

- RISJ Digital News Report 2024: Three essential points for your newsroom

- RISJ Digital News Report 2024: Five trends to watch in the UK

- Standing out in a crowded market: what makes a top news podcast?

- Gender equity in the newsroom, with Luba Kassova