A study by the think tank Demos earlier this year revealed female journalists receive roughly three times as much abuse on Twitter as their male counterparts.

Demos analysed more than 2 million tweets sent to celebrities, politicians, musicians and journalists over a two-week period. Journalism was the only category where women were more likely to be on the receiving end of Twitter abuse than men.

Speaking to Journalism.co.uk, Carl Miller, research director for the Centre for the Analysis of Social Media and a co-author of the report, explained that "we're struggling with a new phenomenon here".

"We've opened up these new digital spaces and in lots of different ways people are not treating others civilly and as well as they would offline," Miller said.

According to the Demos report, around five per cent of the tweets a female journalist receives are derogatory or abusive, compared to under two per cent for male journalists.

What's more, the abuse directed at women reporters is far more likely to be sexualised or based on appearance than that directed at men.

"It's really hard to tell why this scale of misogyny exists online," he said, "and why it's particularly directed at journalists and not other prominent women."

In this story, three female journalists share their experiences of online abuse and how they handled it.

The video game reviewer

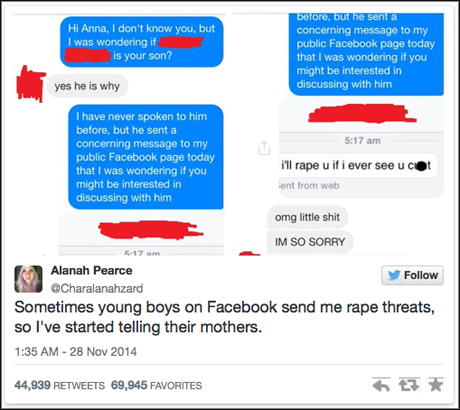

In Brisbane, Australia, Alanah Pearce, who reviews video games for the online TV show Button Bash and the radio show 4zzz, got fed up with the rape threats and sexually violent messages she was consistently receiving on Facebook from teenage boys.

So she decided to contact their mothers.

Screenshot from Twitter, red censorship by Pearce, black censorship by Journalism.co.uk

"I probably started getting sexual harassment online as soon as I started reviewing games in the public eye, which was about three years ago," explained Pearce.

"And for the most part I've always ignored it, everyone always tells you to ignore the trolls or ignore the haters, and it go to the point where I was just kind of frustrated with letting them win and letting them get away with it."

Pearce noted the abuse is increasing as she gets more “social media reach” – she has 30,000 ‘likes’ on her Facebook Page and more than 50,000 subscribers on YouTube.

The abuse becomes more frequent if she posts a controversial video review, although she is quick to point out that these comments are just a handful compared to the more positive messages she usually gets.

Pearce’s experience is part of a wider issue around misogyny and harassment in video game culture, of which perhaps the best example is this year’s Gamergate controversy.

In forwarding the offensive messages she receives to the perpetuator's moms, she said she not only hopes to "troll back the trolls" but also "to actually give them real-world consequences for things they're saying online that they assume don't matter or could never come back to them".For a lot of people the idea that a woman has strong views is still very unpalatableSonia Faleiro, journalist and founder of Deca

While this approach isn't for anyone, Miller said that reminding people who post abuse that they are "dealing with other human beings" can be effective in making them think twice about their actions.

People who post offensive comments online experience something known as 'cognitive disinhibition', he explained, where technology acts as shield for behavior they might not normally display.

"When you're sat staring at a screen, the abuse that you send is like the abuse that you'd shout at a television, rather than something you'd actually shout face-to-face in a pub," he said.

While he noted humanising the process was not a "golden bullet" he said it did seem to lower the severity of the abuse.

The political journalist

Women are also often targeted for writing about subjects not traditionally seen as 'feminine', such as politics.

Sonia Faleiro, journalist and co-founder of the long-form journalism co-operative Deca, received abuse after writing a story for the New York Times on the so-called phenomenon known as "love jihad".

The article reveals false claims, which Faleiro explained have been disproved by both the courts and the police, that Muslims in India are attempting to impregnate Hindu women in the hope of turning the country into a Muslim nation.

After the article was published in October, Faleiro received a number of offensive tweets and emails.

"For a lot of people the idea that a woman has strong views is still very unpalatable, especially when those views are political, especially when those views are liberal, and especially when the woman journalist in particular has a platform. I think that seems to incite envy as well," she said.

"I've noticed over the last couple of years, any time I have a piece that deals with a political situation I receive an incredible amount of abuse.A lot of the pleasure for them comes from feeling like they've been noticed, like they've had an impactSonia Faleiro, Deca

"These people are clearly Googling me and finding out intimate details about my family."

This was not the first time Faleiro had encountered this kind of abuse, although she recognises that the often political nature of the stories she writes has a tendency to aggravate the more conservative or right-wing factions of society.

"Talking down to women is something you see at so many levels... the abuse is essentially telling me that I don't know what I'm talking about, that I shouldn't be reporting on these things, and a sort of pat on the back, you know, go back and write about cooking and other ladylike things, don't talk about politics."

When it comes to dealing with abusive tweets, Faleiro believes that the best way to respond is to block the offending accounts.

"A lot of the pleasure comes from engaging with the person you're attacking, a lot of the pleasure for them comes from feeling like they've been noticed, like they've had an impact, and so I simply block them so I have no idea what they' are saying... I don't need to see it because it's not criticism that is relevant to me."

The UsVsTh3m journalist

When Abi Wilkinson, a journalist at the Trinity Mirror site UsVsTh3m, posted a tweet criticising the controversial TV personality Dapper Laughs, whose Christmas album, which claimed to raise money for the homelessness charity Shelter, included a reference to a "tramp" smelling like "shit".

When the so-called comedian, real name Daniel O'Reilly, responded with a tweet (since deleted) claiming Wilksinson was trying to "slate" his "angle on helping homeless people", the barrage of abuse she received from his followers took everyone by surprise – not least Wilkinson herself.

.@DapperLaughs has literally put out a song where he shouts at a 'tramp' "you smell like shit" because he wants to help homeless people.

— Abi Wilkinson (@AbiWilks) November 6, 2014

An example of the abusive tweets received by Abi Wilkinson

Wilkinson set her Twitter account to only see notifications from people she followed and asked her boyfriend to delete any offensive Facebook messages on her account.

She also ignored the unusually high number of Facebook and Instagram friend requests she received, which she described as "a bit weird, because it was like people were snooping on me".

She tried turning off her phone to avoid the abuse, but then became anxious about what was being said online without her knowledge.

"It did make it quite hard to get to sleep that evening," she said.

It was later alleged by some Twitter users that O'Reilly had used Snapchat to encourage his fans to send the abusive messages.

What's interesting here is that O'Reilly also tweeted about Wilksinson's colleague Nathaniel Tapley, who'd written a scathing review of the Christmas album.

So how did the abuse directed at her differ from the abuse directed at him?

"I maybe got a little bit more [abuse] than he did – he got a lot – but I guess what was different was the kind of stuff I got," explained Wilkinson.

"There were a lot of like, not credible rape threats, but there were things like that. There were a lot of comments about sluttiness - 'slut' this, 'slag' that, loads of comments about my appearance.

"There was lots of sexually violent stuff, whereas the insults Natt was getting were more... they weren't gendered I guess."

The law

Under current UK law, anyone convicted of posting abusive message online can face a jail sentence of up to six months.

However last month Justice Secretary Chris Grayling proposed new laws to tackle those who post abusive messages online, which would extend the maximum jail term for the offence to up to two years.

The Crown Office also recently laid out new guidelines for prosecuting those who post abusive messages on social media, promising a “robust” response.

And at the start of December, Twitter announced it will be making it easier for users to report harassment, in addition to improvements to its "block" function, which will be rolled out over the next few weeks.

Writing on the Twitter blog, Shreyas Doshi, director of product management, noted that "everything that happens in the real world, happens on Twitter".

However, unlike in the "real world" social media platforms offers a much greater opportunity to harass or abuse people – particularly, it seems, if you're a female journalist.

- Online abuse aimed at female journalists is also the subject of this Journalism.co.uk podcast.

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).

Related articles

- Journalists are happy to be disconnecting from platforms, should news organisations be worried?

- Protecting journalists on social media, with Valérie Bélair-Gagnon

- 10 creative ways to interview celebrities and experts

- Open letter calls for a change in response to online abuse of women journalists

- What will your audience want in the future?