The Marshall Project, a non-profit news organisation that covers the criminal justice system in the United States, has developed a free and open-source tool that allows reporters and editors to track websites of interest and receive notifications via Slack or email when newsworthy changes happen.

The news organisation has been using the tool, called Klaxon, internally for more than two years, and the latest public version was made available last month, after The Marshall Project had already received some feedback from early adopters.

The installation instructions are available on GitHub and Klaxon is hosted on a platform called Heroku, although it can also be set up on a different server according to each newsroom's preferences.

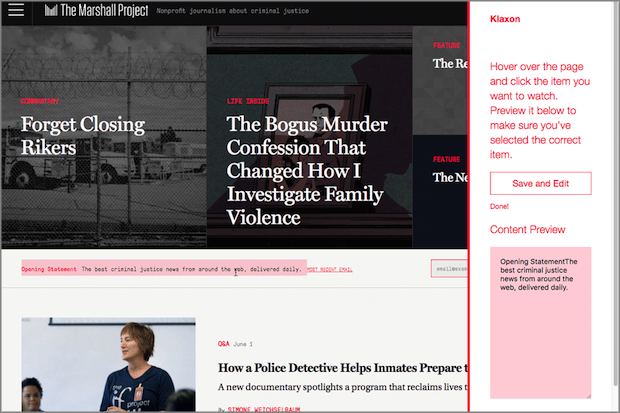

Once installed, Klaxon will show up as a bookmarklet in the web browser's bookmarks bar. When a reporter is accessing a website they would like to monitor, all they have to do is click the Klaxon icon, hover over the section of the website they want to track and click to select it.

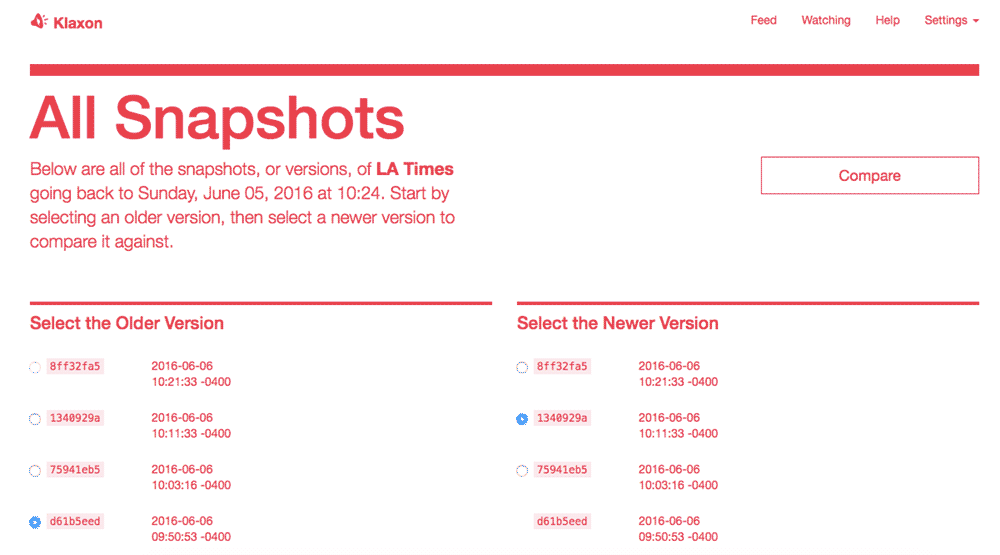

All the websites that are monitored are listed in the Klaxon dashboard, and the tool goes back and visits each one of them roughly every 10 minutes, explained Tom Meagher, deputy managing editor at The Marshall Project.

"We realised there's a lot of noise happening and websites change all the time, especially on government websites. But you don't necessarily care about 90 per cent of a government website, so we wanted to be able to track just this particular data set or this one column of information."

When the tool notices any changes on a website, it sends an alert to the reporter who set it up via email or Slack – other people in the newsroom can also subscribe to receive the same alerts.

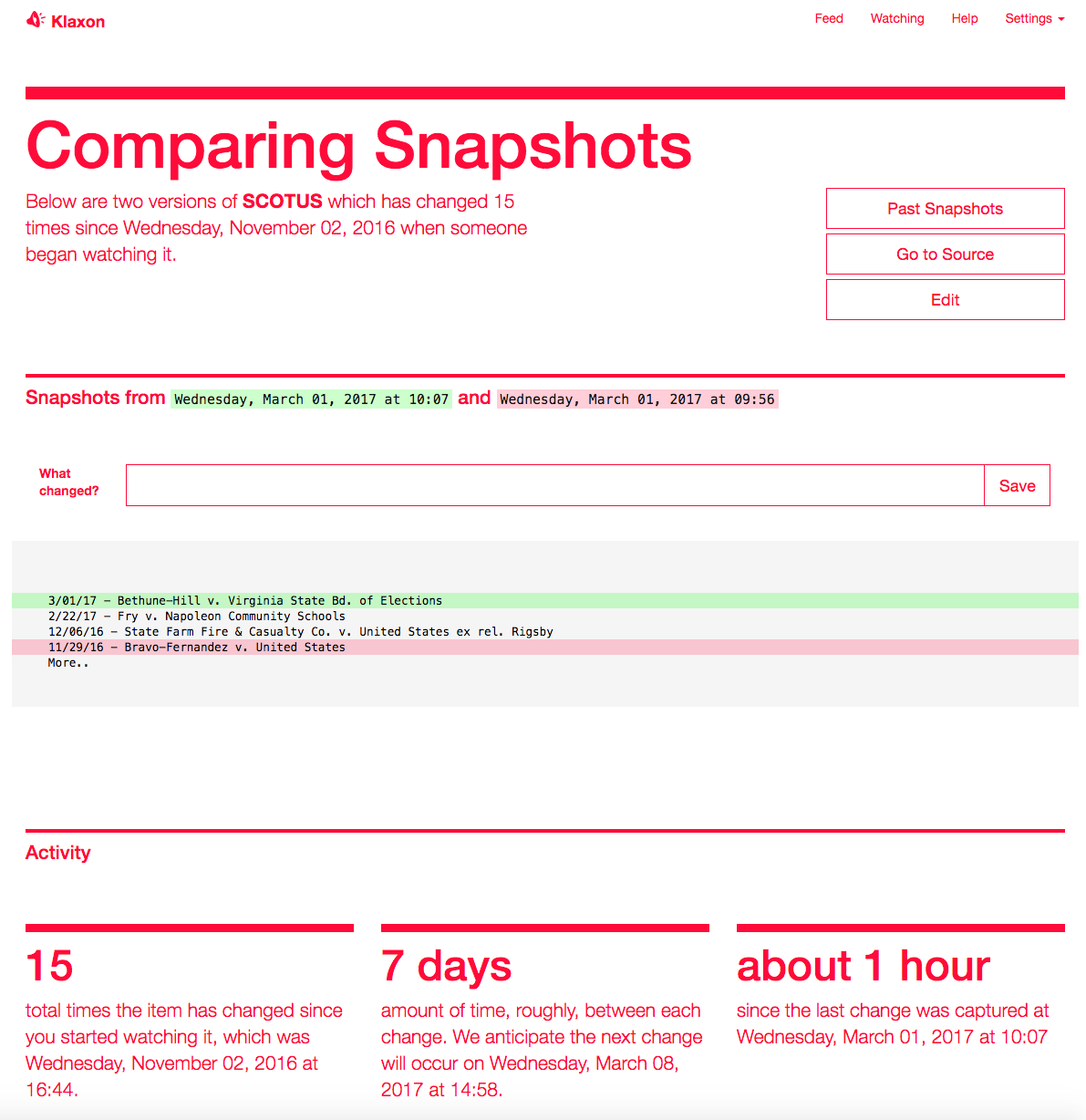

The alerts contain a link to the update in Klaxon as well as a visual representation of what has changed, with snapshots of the website or page outlining in red the information that has been removed and in green the new data that has been added.

The Marshall Project has used Klaxon in a variety of data-driven reporting, for example to track data about a programme from the US Department of Defense that shares military service equipment with police departments, or to watch some of the executive orders put out by President Trump in his first weeks in office.

"We noticed that occasionally they were going back and rewording things, massaging slight misinformation. And that didn't lead to a story but we put it on social media and shared it with our network and our readers to tell them we are paying attention to this," Meagher said.

"Ultimately what we're doing is monitoring public websites, so you're not necessarily going to find an investigative bombshell, but we found it's really useful for getting quick tips, as well as monitoring multiple websites at once.

"You could put 50 different websites on a particular beat on it and everything comes to you, and particularly in a small newsroom where reporters are trying to cover a lot of ground, it's super helpful to outsource some of that and not having to go every day and check yourself if something has changed."

The Marshall Project started building Klaxon in 2014, shortly after the organisation launched, when the team was looking to develop a calendar or interactive graphic to help visualise executions in the US.

They came across the Death Penalty Information Center, a non-profit group based in Washington that focuses on studies and reports related to the death penalty. While their database seemed like a suitable data source for the project, reporters also needed to find out quickly when the website was updated and what had changed.

Meagher originally thought of creating a custom scraper to track changes, but since this issue could arise again in the future, he worked with the organisation's director of technology to build a tool to track website updates.

The initial version ended up being used to monitor "dozens of websites of government agencies in a bunch of different states", but even though it was a good proof of concept, it was too complicated to be use by non-technical journalists in the newsroom, he added.

A new version was developed a few months later, with an interface that allowed individual reporters to add the websites they wanted to track. It was used for over a year in the newsroom, including to develop the project 'The next to die', which monitors executions to help provide more comprehensive coverage of capital punishment in the US.

"We realised it could be really useful for other newsrooms and, as a non-profit, we wanted to be able to share our knowledge and to share tools we thought would make this investigative reporting job easier for other journalists."

Klaxon was rebuilt from scratch last spring during an OpenNews code convening. In autumn 2016, The Marshall Project made a beta version available to newsroom developers.

Since then, journalists from The New York Times, The Texas Tribune and The Washington Post as well as reporters in Europe and Australia have used Klaxon and contributed to the code on GitHub, which "has been useful to get it robust enough for us to be comfortable with everybody using it".

"One thing we'd like to think more about is how it works in larger news organisations, because we designed for a smaller team like ours, so we need to think about the user interface and how people interact with the tool if there are dozens using it.

"We're excited about the possibility of other journalists contributing to the project so if people are interested in using it, we'd love to hear from them."

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).

Related articles

- Three free AI-powered transcription tools for journalists

- New investigative project helps resource-poor newsrooms report on health

- New global network investigates obstacles to climate action

- Investigating human trafficking, with ICIJ lead reporter Katie McQue

- Six credibility markers for journalists and news sites