Interactive stories have become the norm among major news organisations and big or contentious issues often get a significant digital treatment.

That doesn't always mean it is done well, however, and sometimes news organisations or journalists can use interactive measures without fully considering what they are trying to achieve, according to Sandra Gaudenzi, lecturer in interactive media at the London College of Media.

"Why use interactivity? What should I do?," she said today at the Centre for Investigative Journalism's Summer Conference. "How does interactivity allow users to make a shift in what they know, what they feel, that maybe a linear story would be less effective in doing?"

Interactivity should offer a degree of agency and participation to the reader, said Gaudenzi, but in doing so the author relinquishes a certain amount of control over where that story goes.

This "spectrum of interactivity" is being explored more and more by news organisations but journalists and storytellers should always think of what interaction brings to the story and the balance of control between reader and author.

"Using interactivity just for the sake of it is really boring," she said, "So think about what the user might want to do or need to do to feel a part of the story."

She detailed examples across three parts of the spectrum: keeping the storyteller in control of the story, letting readers shape the narrative, and giving the audience a platform to tell their own stories.

1. Telling media-rich, linear stories

Embellishing and enhancing traditional text-based stories with multimedia elements is a common way for news organisations and storytellers to deliver more interactivity in their work.

The New York Times's oft-cited 'Snowfall' article was an early example that received a lot of attention, Gaudenzi said, and the Guardian pushed the format further in 2013 with 'Firestorm', a piece about Australian bushfires, and with last year's 'The shirt on your back', about Bangladeshi garment factories.

Screengrab from 'The shirt on your back'.

But in essence it is still a linear story that allows the author to retain control over almost all elements of its telling.

Newsgames and stories that give more agency to their readers take steps away from the author while still keeping the story within pre-set boundaries.

'Journey to the centre of coal' is an award-winning interactive documentary, produced for Le Monde in 2008, that takes the 'choose your own adventure' style of branching narrative to let users explore the lives of coal miners in China.

'Inside the Haiti earthquake' continued in a similar vein in 2010, but users could explore the story from the perspective of a survivor, an aid worker or a journalist, while Al Jazeera's 'Pirate Fishing' interactive went all out in giving users targets, badges and other game elements.

A simpler format in this media-rich category gave users the ability to hear a single story illustrated in different ways, exemplified by the story of Alma, a former gang member from Guatemala.

Users had the choice of watching Alma tell her horrifying stories of gang life or view accompanying images that tell the tale.

The elements are very basic, said Gaudenzi, in incorporating just a single audio track and two video tracks, but the effect goes much further than the individual parts while still giving the user a degree of agency in how the story is told.

2. Become a curator and present other points of view

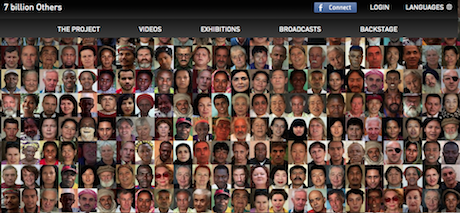

The 'mosaic' style of presenting videos without a clear structure was particularly effective in '7 billion others', said Gaudenzi, taking on the big topic of "what it means to be human in this modern, digital world".

"They interviewed 500 people and then accepted participation from anyone answering a set of 40 questions," she said. "What do you believe in? What are you afraid of? What is love? What is death? And each person gives an answer."

Viewers can click on interviewees to hear their views, and can jump between different topics like memories or happiness, hearing what the concepts mean to people in different parts of the world.

"Here the concept is to go for curation," Gaudenzi said. "You set the questions and then open it up for people to participate."

Screenshot from 7 Billion Others.

3. Become a facilitator for others

At the top end of Gaudenzi's "interactivity spectrum" are projects which act more as a platform for users to express themselves and tell their own stories, creating a space for discussion.

The Question Bridge project asked contributors to submit questions about being black and male in America. People could record themselves asking a question and then anyone else could answer by submitting their own video.

This personal involvement is important but it can be also be automated. Indeed, the data-mining elements of personalisation used by companies like Google and Facebook needn't only be used to target advertising.

"Storytellers have started to think 'how do we make this more relevant to the user and give them a role in the story?'," she said.

The Do Not Track project aimed to give users an idea of how much data they freely give up when browsing online by using that exact information to tell the story.

As soon as someone hits play, information about the user's location is sent to the player, and Do Not Track picks out information relevant to that location.

For example, a viewer in London would receive images and video clips relevant to the location, local time, weather and recent news while the narrator explains the process.

As the video continues and viewers input information about the browsing habits, Do Not Track continues to build a picture and personalise the story dependent on each individual.

"This is still journalism but with a different logic," Gaudenzi said. "We talk about [data-mining] as something that is big and nasty and abstract but what about you? What does it mean to you?"

Human interest and relevance have long been the hooks on which journalists frame stories of large, important or abstract topics, but personalising the news goes a step further in helping audiences understand.

The other side of the personalisation coin is in immersing the audience in the experience of someone else, and virtual reality could allow journalists to achieve this like never before, Gaudenzi said.

Clouds over Sidra is one of the best know examples of VR in news, putting the viewer in the shoes of a 12-year old Syrian refugee living in a camp of thousands.

The type of 360 photos put forward by film-maker Chris Milk are a simpler example of the same idea, while films like the forthcoming The Enemy take leaps forward in virtual reality for news by portraying the experiences of people on either side of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

"The form the story takes can be so many things," Gaudenzi said, "and although technology allows us to do so many things, the problem is always the same – why should we?"

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).

Related articles

- The Big Issue experiments with interactive storytelling to help readers explore homelessness

- Mobile-first mag Frame helps younger audiences engage with the news

- 'When you're surrounded by something constantly, it stops surprising you': The Washington Post Magazine experiments with storytelling through poems, songs and board games

- NYT uses new interactive design to report on sexual consent on campuses

- Tool for journalists: InterviewJS, for turning interviews into interactive chats