Mohamed Belmaaza is a data analyst at Les Echos, France’s main business news organisation, where he spends his time swinging between issues related to editorial strategies, audience development, conceptual projects and advertising. He is interested in understanding the evolving behaviours of readers online, and the following piece outlines his takeaways from observing the coverage of the Paris attacks and the way people looked for information online.

What a difference weekdays and weekends make for covering tragic events. I remember the Charlie Hebdo shootings, it was a Wednesday and most people were at the office or at school.

But during the attacks in Paris on Friday, people were able to stay safely at home and to remain so throughout the weekend. This meant they were likely to sit in front of their TVs, watching the news – and understanding this context is key.

Friday night, I was among the luckiest. I decided to spend my evening at home watching a film on Netflix. When I first got an app notification from France 24 about a shooting in Paris, my reaction was to immediately jump on Twitter to check what was going on: panic everywhere but nothing clear. I then decided to switch to France 24 to get news and to follow the events as they were happening.

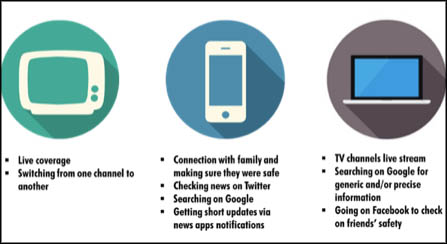

So my night was spent switching between those two screens, TV for live coverage and my iPhone (and from time to time my laptop as well) for Facebook, Twitter and Google.

My behaviour is quite typical – according to a study published by Discovery Communications in November 2014, people are more likely to multi-task on their smartphones while watching TV.

And this is even more important to understand in the context of the terrorist attacks last week. The findings could help the media imagine how people, in a state of panic, would switch even more frequently from one screen to another, to follow the news as it is happening.

This consideration is a game changer for live coverage on news websites.

Live reports on webpages became secondary, as people were already following the coverage on television.

In this case, news websites should then focus on creating valuable content by publishing information complementary to what the reader is already getting on TV.

Moreover, people on both social networks and search engines have specific queries, and they expect answers to confirm or debunk rumours and be precise. A clear example would be the audience reaction to President Hollande declaring a state of emergency –people immediately rushed to Google to understand what this was about.

Live data from Google Trends.

Secondly, as mobile traffic mainly comes from Google and social networks, readers need to get short and simple articles with direct answers to their questions, instead of longer pieces with an 'infinite scroll' format.

And these readers land directly on articles, without going through the homepage. This means newsrooms can spend less time and energy on editing the homepage, but also that they need to make more of an effort in order to retain their readers' attention.

French daily newspaper Le Monde focused on explaining what was happening on Friday. They started a live blog, with both last minute updates and a separate section that provided a summary of the confirmed facts.

Screenshots of Le Monde live blog; left: the facts; right: live updates.

But they also made it possible for readers to interact with the updates by asking direct questions.

That was a precious tool for people to access during difficult times like those of last week, and also for the newsroom, as it was gathering real-time information, ahead of all competitors, to help journalists explain the news and answer key questions about the ongoing events.

Le Monde also translated articles to foreign languages, and dedicated Les Décodeurs, its data-driven journalism section, to debunking the fake information which aimed to “maintain psychosis, generate buzz, as well as to propagate fake information in order for it to fuel hatred”. France 24 also published several updates on its fact-checking section, The Observers.

In the United States, The New York Times offered readers the possibility to subscribe to updates via email, to make them more engaged and expose them to a larger range of content related to the Paris attacks. It also represented a way to keep readers who might have come from social networks and search engines interested for longer.

So in order for newsrooms to efficiently cover terror attacks and other tragic events, it is very important for them to understand the shift in the way information is consumed.

Events like those in Paris quickly disrupt most of what we know about the behaviours of readers online, and it is among the fundamental challenges news organisations are facing today to be able to quickly understand the precise context in which those events are happening, and to quickly adapt to this context.

Mohamed Belmaaza also writes about culture, geopolitics and Middle Eastern art. He tweets in French, English, Arabic and Hebrew @mohamedblmz.

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).