This article first appeared on the French and English editions of the European Journalism Observatory (EJO) and is republished here with permission.

Facebook has won. French media organisations are now indeed addicts. They are, in fact, triply addicted – to expanding their audience for free, to using the social network’s production and distribution tools, and to earning additional revenue. Facebook’s publishing ecosystem has become something the media can’t do without.

From the innocent, playful quest for “likes” of the early years to the paid, made-to-order videos of today, the audience dealer has done its job well. Hit by hit, publishers have sealed a tacit pact with the platform, a pact that can be compared to a marriage of convenience. The bride’s dowry comes with two billion users. The down-and-out bridegroom couldn’t have asked for more.

Floundering financially and abandoned by their reader base, traditional media outfits have received an unexpected shot in the arm from the audience offered by Facebook. High on rosy statistics, publishers convinced themselves they couldn’t go wrong with an audience so clearly receptive to their content. They had found the El Dorado of internet users just in time.

But their comedown is already in sight. Facebook clearly intends to burst this enchanted bubble by adding a price tag for the companies most hooked on likes and the traffic Facebook generated for their sites. Every day, editorial staff are hard at work producing content designed specifically for the platform.

What repercussions will this voluntary servitude have for the daily operations of newsrooms, both big and small? What will the consequences be for the teams working to fill Facebook news feeds, particularly with on-demand and live video? And above all, how did the social network manage to convince so many media outlets at the end of their financial ropes to work for its platform? Let’s take a closer look at the formidable strategy that’s putting the agility of editorial staff to the test.

The publisher-as-publicist strategy

In October, Facebook fired a warning shot to all those who thought they had found a free way to directly access a mass captive audience. By testing out a separate news feed for non-sponsored posts from business pages (outside the classic news feed for posts from friends and family, sponsored content and advertisements), Facebook sent a clear message to brands, businesses, organisations, non-profits and media companies looking for visibility: nothing is free.

The move came despite the fact that publishers are working more than ever before for the social network and creating more custom content than ever to feed users’ timelines.

The size of the audience involved is alone not enough to explain this sudden and unparalleled productivity. Since June 2016, Facebook has been paying several major American media outlets to flood news feeds with original content and serve as its technical and advertising laboratory.

To entice media companies, Mark Zuckerberg has in essence created a network of major publishers that can serve as publicity for the incredible effectiveness of the new formats on the market.

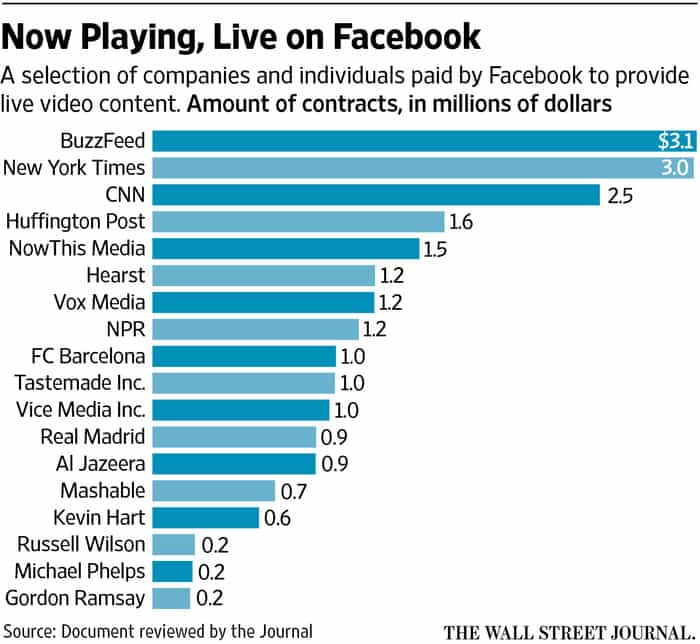

The Facebook founder’s “dream team” of media heavyweights includes The New York Times, CNN, HuffPost, BuzzFeed, Vox, Mashable and even Condé Nast.

These media outlets are models of digital-market success with solid reputations. They are capable of large-scale production, and their content is read the world over.

To convince them to participate, Facebook had to exercise its powers of persuasion. According to a document brought to light by the Wall Street Journal in June 2016, Mark Zuckerberg put 50 million dollars into 140 partnerships with media outfits and celebrities, with 17 of those contracts being worth over a million dollars (NYT's and BuzzFeed’s were just over three million, and CNN’s was two and a half million). That’s just a drop in the ocean compared to Facebook’s 10 billion dollars in quarterly revenue, up 47 per cent from the same quarter last year.

The deal is simple: the partners receive a certain sum and, in exchange, must produce massive amounts of high-value-added content on the platform, including video, Facebook Live, 360, and Instant Articles. They are being paid to inundate news feeds with original content, which should convince all other publishers to follow suit.

French media companies get millions of euros

The strategy has proved very effective. The outlets enlisted are big names and that, combined with powerful algorithms, has helped make the new formats worldwide norms in less than a year. Tempted by the volumes of clicks, publishers around the world have jumped into the fray, thereby crowning Facebook’s strategy a success.

And by no means is the plan limited to the US. In Europe, major French media companies are among those getting involved in the large-scale game of seduction.

TF1, Le Figaro, Le Parisien and the Le Monde Group’s titles are all among the outlets getting paid to produce video content for Facebook. And the sums involved are staggering – companies sign on for renewable six-month terms and receive between 100,000 and 200,000 euros per month, according to several sources.

Given that most of the above outfits (a non-exhaustive list) have already renewed their partnerships once, the money going from Facebook to French media is in the millions of euros.

It goes without saying that the editorial staff we contacted were less than forthcoming with the details of these confidential agreements. But even if the terms change from one media outlet to the next, the principle remains the same: in exchange for the money it receives, each outlet commits to producing a specific volume of on-demand and/or live video content over a given period, according to the information we have been able to gather.

At the news channel LCI, for example, editorial staff must produce 14 hours of live programming each month, and each segment must be between six and 20 minutes in duration. Sources inside the company say these precise requirements must be observed, as they are checked closely.

It’s also in the channel’s best interest to keep on good terms with its sponsor. According to one employee, the money Facebook paid over the period in question was enough to fund two-thirds of its web editorial staff.

But Facebook’s financial contributions didn’t stop there. It helped fund a brand new studio so that LCI could stream Facebook Live segments during the presidential campaign. That financial dependence comes on top of the channel’s dependence on referral traffic from the social network, which accounts for 30 to 40 per cent of visits to its website.

RTL also used Facebook’s money for its live-streaming studio, and Europe 1 put them into a Facebook Room and an Instagram Story Studio installed on a bus that criss-crossed France during the election season.

The support provided by Facebook to media companies also takes the form of technical advice on how to most effectively exploit the algorithm that ranks posts and on understanding the finer points of audience statistics. This includes giving the companies access to CrowdTangle, a proprietary tool for analysing traffic.

As for Facebook, they acknowledge their financial contributions but minimise their importance. “Seeing Facebook’s collaborations only through the lens of its paid partnerships is reductive. Our role is to work together with media outlets on a daily basis to develop tools aimed at enhancing their experience on Facebook. This happens with a lot of back-and-forth and test phases where we have sometimes compensated our partners. The media outlets take the time to use our new products and share their feedback with us, so it seems natural to us that they be compensated for that. This always occurs on a temporary basis during the test phase,” explains Edouard Braud, head of media partnerships for Southern Europe.

A win-win approach?

After a painful beginning, clumsy communication and excessively restrictive specifications, Facebook has been making massive investments in its media relationships since 2010. The Media Partnership Team is launching increasing numbers of newsroom initiatives, such as the Facebook Journalism Project and the Listening Tour that kicked off in June 2017.

While the media regularly sound the alarm about dependence on billionaire shareholders or close ties with politicians, dependence on Facebook does not seem to worry them too much. On the contrary, the partnerships are perceived as prime opportunities for experimenting and getting closer to their audience.

Aurélien Viers, head of visual content at the news magazine L’Obs, is enthusiastic: “The partnership allows us to go further in our experimenting without turning our organisation upside down. Thanks to the tools provided, we’ve been able to create original video formats that have been quite successful online. Livestreaming regularly from the field for social media has led to a new, more spontaneous and dynamic relationship with our audience. You could say that Facebook condenses all the new video-related challenges, in terms of storytelling, creativity and the ability to set yourself apart in a very competitive environment.”

But behind the scenes, teeth are being gnashed at the partner outlets, especially in advertising and sales departments that are involved in a fierce and fruitless struggle with their principal competitor, the behemoth Facebook. “Faced with Facebook’s ‘suitcases of cash’, the advertising departments have trouble being heard,” explained one journalist off the record. “And when Facebook tests out its new mid-roll advertisements on our own productions, the exasperation peaks.”

The platform’s efficiency is cause for despair for publishers that are bogged down in (overly) complex audience-retention strategies. As one head of digital content explains: “If, in order to watch a video on a site, an internet user has to click on a link, wait several, very long seconds for the page to load, close one or two advertising windows and then finally sit through a thirty-second ad, there’s no question, we can’t compete. We’re not playing in the same league as Facebook and its instantaneous autoplay.”

Michaël Szadkowski, editor-in-chief of Le Monde’s website and social networks, said they made no editorial concessions and kept complete control over content, a 'sine qua non' of the partnership: “The money we were paid has not fundamentally changed how we work. Video production was already a priority for us, with a dedicated team of 15 people. We post more content than before on the platform – that is true – but I prefer for Facebook to provide support to the media rather than for it to start creating and imposing its own content. Facebook has grown, its directors have realised that they can’t keep asking media companies to produce free, high-value content and then make advertising money from that content.” That observation, however, holds true only for its partners and for a limited time frame.

Guillaume Lacroix, co-founder of Brut, a video production company only present on social media, sings the praises of his company’s collaboration with Facebook, calling it a “working relationship” without any financial component. “Facebook gives us a great deal of helpful advice on how to get greater engagement on our videos. They also tell us about the formats in vogue around the world. In September, for example, we were invited to Dublin to take part in a conference that brought together 35 media companies that got their start online. We learned a lot from each other. In addition, Facebook makes CrowdTangle available to us – it’s a very effective tool that analyzes audience engagement on social networks. If we had to pay to use it, I’m not sure we’d be able to afford it.”

Like Le Monde and L’Obs, Brut sees its collaboration with Facebook as a true competitive advantage and believes that the model will last: “It doesn’t scare us to be Facebook-dependent, no more so than a producer who only works with one television station. Also, the fact that Brut will be profitable in 2018 even though they don’t give us money means that there is a social media business model.”

Edouard Braud says Facebook does everything to give outlets the greatest autonomy: “All our products are made in such a way that they don’t generate any dependence. We design them so that they will enhance the outlets’ experience and help them create value thanks to Facebook. That can be done both inside our environment and outside it. That’s why we develop tools that allow value creation in outlets’ proprietary environments, like the modules on Instant Articles for subscribing to newsletters, downloading apps, and so on.”

A decoy and a danger for small media outfits

Apart from its media partners, there are few newsrooms with the resources and flexibility needed to take on Facebook’s requirements. In the absence of a financial incentive or revenue compensating content produced for the social network, small media companies are running out of steam as they try to capitalise on the audience and the powerful tools at their disposal.

The result is the gradual establishment of a two-speed ecosystem, reinforced by media companies’ kamikaze strategy, of which their video productions are an illuminating example. There are multiple reasons why most outlets have little to gain from getting into the production of video for social media:

- Video production is complex, time-consuming and costly, especially for print press not usually in that field. Putting a special workflow into place and training or hiring journalists capable of filming and editing videos for social media represents a considerable cost. In this field, profitability is often still just a dream.

- The content is dazzlingly professional. Videos posted on Facebook look more and more like TV productions, which tends to sideline outlets unable to meet the prevailing quality standards. Today, most Facebook live-streaming is done with several cameras and a director.

- The recommended formats are subject to change. For six months, Facebook wants videos that last less than a minute and can be viewed without sound. The next month, sequences have to last at least a minute and thirty seconds, and if they don’t the algorithm might reject them. Just thirty short seconds more and the formats have to be re-thought and the production chain reorganised.

- Engagement is paradoxical. Experience shows video content posted on Facebook brings the least amount of traffic to publishers’ sites. The videos generate strong engagement but are watched only in news feeds and rarely on the websites. Nevertheless, media companies are stepping up their efforts to produce native, unprofitable videos. But, as on YouTube, the news is far from ranking among the most-watched content on Facebook.

- Audience data is deceptive. Understanding and analysing Facebook’s figures on engagement requires patience and solid skills, and the reliability of those figures should not be taken for granted. In 2016, Facebook admitted to having overstated statistics on video views by 60 to 80 per cent – over the course of two years! A “technical error” was invoked. This inane excuse might make us laugh if it weren’t for the enormous impact it had on advertising spending and the funds earmarked by media companies for video production. When a company reaches several hundreds of thousands or even millions of views per video, the margins of error aren’t that meaningful, but when a video strategy is assessed on the basis of a few thousand clicks, the repercussions can be quite serious.

- The desire to maintain reach and the temptation to boost posts can be strong. The fact that all the players are present on the platform is creating a new race for attention, and the result is saturated timelines and a decrease in the visibility of content, intelligently orchestrated by Facebook. A significant drop in publications’ reach can contribute to the destabilisation of media companies’ fragile business models. And the temptation to pay to maintain their popularity, generously granted by the platform, is no longer the exception in newsrooms. Sponsored content is on the rise and media companies are now becoming the clientele of Facebook’s advertising department.

Facebook has won

The many paradoxes mentioned above are the best proof that Facebook has won. The media’s voluntary servitude can be analysed through the lens of their financial situation, but it is difficult to say what the long-term consequences will be. Are they unavoidable sacrifices on the altar of the digital transition? Perhaps, but we must remember that the dependence is not just financial. Media companies are also dependent technically, for access to production and distribution tools.

The weight of this dependence is affecting content and contributing to the uniformity of formats worldwide. Above all, the dependence is influencing the organisation and daily operations of editorial staffs and is setting their pace.

French media regularly sound the alarms over the lack of media independence in the face of billionaire industrialist shareholders. However, those same media companies are allowing a menace to be gradually introduced that is equally toxic to the future of the outlets and democracy itself – the menace of soft power, money and the GAFA (Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple) ecosystem.

Update 15/12: According to a Digiday article published on 13 December, Facebook plans to stop paying publishers to make news feed videos, as most of the contracts the company had with these outlets are set to expire at the end of 2017 and they will not be renewed.

Nicolas Becquet is a journalist and digital platforms manager for the Belgian daily L'Echo. He blogs at mediatype.be.

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).

Related articles

- How do journalists really want to use generative AI?

- What AI can do for your newsroom: tips from Ring Publishing's latest handbook

- Journalists are happy to be disconnecting from platforms, should news organisations be worried?

- Creating and developing GenAI workflows in the newsroom, with David Caswell

- Ukrainian journalists are at a breaking point. It is time to make a change