If you want to transfer a piece of information from your brain to another brain and be absolutely sure that no one else will know, here's what you need to do.

Get a pane of glass, a piece of paper and a felt-tip pen. Together with the intended recipient, position yourselves under a tin foil sheet, under a duvet in a closed and windowless room. Put the sheet of paper on the glass and write your message using the felt-tip pen so it doesn't leave an impression, then take the paper, burn it, and flush portions of the ashes down the toilet at three-hour intervals.

This may seem extreme, but information security expert Arjen Kamphuis, speaking at an NUJ event on privacy and security yesterday, said this was possibly the only way to be sure since the revelations about government surveillance were made public last year.There's almost no hardware that we can trust right now that you can buy on the high streetArjen Kamphuis, information security expert

The line between "crazy tinfoil hat" and "really well-informed" has become thinner and thinner, he said, and journalists need to know what risks to their online security exist.

"It is quite difficult for journalists to make any assurances to sources or colleagues that they can communicate securely," he told delegates, "and if you have not protected yourself then those assurances mean very little."

Edward Snowden's NSA files reveal that almost all electronic communications can be intercepted by government agencies or private firms, either directly or by security contractors, so if a journalist is investigating powerful institutions they need to understand that, nine times out of 10, the institution will be aware of the investigation.

The official narrative around internet privacy laws is regularly framed in the context of terrorism or child pornography, but "writing what powerful people don't want written means you have something to hide," Kamphuis said.

Drawing on the free ebook he recently published through The Centre for Investigative Journalism and years of experience in the sector, Kamphuis explained the liabilities and protections that journalists need to know to communicate more securely.

Liabilities

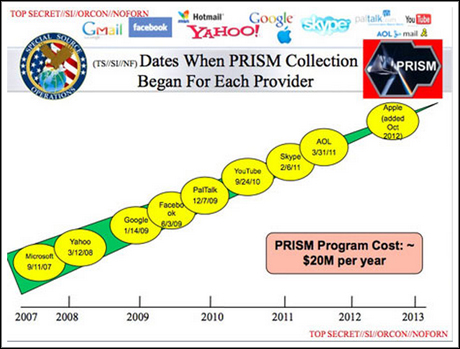

Do you use a product or service from Apple, Microsoft, Google, Yahoo, Facebook, Skype, AOL or PalTalk?

Does your use of those products or services include email, video or voice chat, videos, photos, data storage, voice over IP calls (Skype or similar), file transfers or video conferencing?

If the answer to any part of those questions is yes, your communications are already in the NSA database, Kamphuis said.

Screenshot from Kamphuis's slides, available at Gendo.nl

"Any server, owned or controlled or managed by a US company is, legally speaking, on US territory," Kamphuis said. These servers are where technology and communications companies store the data on their customers' communications and, by US law, the NSA has access to these servers upon request.

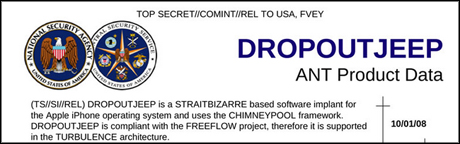

Furthermore, Apple, Microsoft and BlackBerry devices are just some of the technology to which the NSA reportedly has "backdoor access", in addition to other hardware firms like Cisco, Dell, Juniper, Hewlett-Packard and Huawei.

In an extensive report from De Spiegel, the German outlet published NSA documents detailing a range of implants created for mobile devices, keyboards, monitors and computers that let the NSA snoop on the intended users behaviour, upload or download information, or activate different functions without the user knowing.

If a 'target' orders a new device or piece of technology, NSA operatives can intercept the delivery to install the implant, the report says.

Screenshot from Spiegel.de

The companies involved have all protested involvement or knowledge of NSA involvement, and the Washington Post today reported that Apple have announced a new security policy that makes it "not technically feasible" for the company to "respond to government warrants for the extraction of data". Kamphuis still insists on caution.

"There's almost no hardware that we can trust right now that you can buy on the high street," he said.

"You don't know when the different services – Wi-Fi, Bluetooth etc. – are off. The logo on the screen is just what you are being told, it has no relationship with technical reality."

These are among the highest levels of personal surveillance on the planet, but if journalists are going to investigate such powers then they must be aware and protected.

The levels of surveillance or attempts to surreptitiously access investigation data will vary depending on the subject, Kamphuis said. But if it is powerful enough to warrant investigation – governments, corporations, organised crime – it is powerful enough to have its own information security. Just as journalists should.

So how can journalists protect themselves?

Protocol

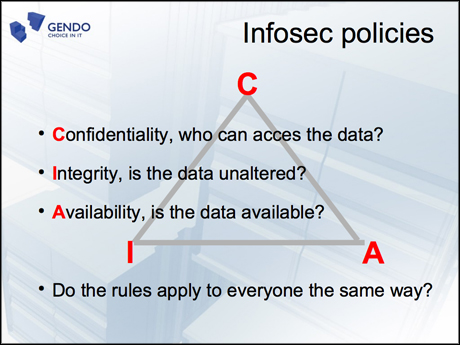

Firstly, the team in an investigation need to be aware of the risks and protections relevant to their role in the team, said Kamphuis, using the mnemonic 'CIA'.

Screenshot from Kamphuis's slides, available at Gendo.nl

From there, the security of the data relies on the behaviour and technology of the team to make it strong.

"It takes a lot of effort to do this right and to do it right all the time," he said. "But if you have a six-month project and you are actually doing something serious – with governments – then you need this."

Web domains

"Any .com address is American territory," Kamphuis said, and the same applies to .net or .org addresses. Just as with physical servers of US companies, they can be accessed by NSA agencies on request.

Instead, choose a domain name from a country with more stringent privacy and security laws, such as .ch (Switzerland), .de (Germany) or .nl (the Netherlands), for a website that may store sensitive data.

Hardware and software

The hardware is the base level of security and Kamphuis recommended finding a pre-2009 IBM Thinkpad X60 or X61 as they are "the only laptop modern enough to have modern software systems but old enough to be able replace the low level software," he said.

This is at the top level of risk, where Glenn Greenwald and co. operated in reviewing Snowden's documents, so it is also important to remove all ethernet, modem, Wi-Fi or Bluetooth capabilities to make sure the device is completely offline, although there is obviously a sliding scale dependent on the level of risk.anybody that does anything with any device that connects information at some level is under surveillance at some pointArjen Kamphuis

Buying online, where they may be intercepted during delivery, is also a potential risk, he said, so recommended journalists buy a model from a second-hand shop for cash.

Kamphuis and co-author Silkie Carlo go into more detail on the vulnerabilities of certain hardware and the necessary fixes in the aforementioned book, but he also recommended installing a new operating system.

Linux and Ubuntu are both well-known, open-source alternatives to Windows, but Tails – 'The Amnesiac Incognito Live System' – is designed specifically to be anti-surveillance.

Online anonymity, encrypted e-mail and chat, file encryption and password protection all come as standard, as do open-source word-processing, photo and audio-editing software. Even better, Tails can run from a USB stick, where files could also be stored, leaving no trace of the sensitive work.

Mobile devices offer no such solace, and without removing the battery – impossible on some devices – Kamphuis said it is difficult to trust whether they may be used for surreptitious surveillance even if they appear to be turned off.

He also stressed that journalists needn't abandon all their devices and software in a fit of paranoia. Many of the programs and equipment that may be more vulnerable to hacking or infiltration have some wonderful qualities that more secure replacements may not, but the point is to separate the two, he said.

Work that needs securing should take place in a secure environment. High scores on Flappy Bird and Instagrammed photos of a weekend breakfast are unlikely to interest most hackers.

Web browsers

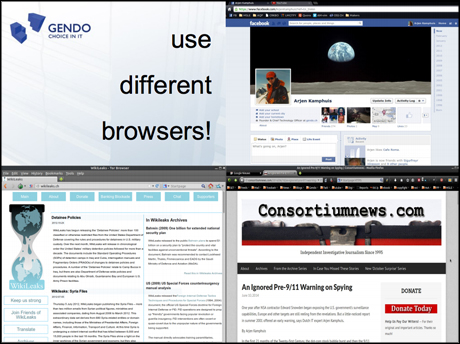

Kamphuis uses three different web browsers, each with differing layers of security expectations.

Screenshot from Kamphuis's slides, available at Gendo.nl

For social media and other uses where there is "no expectation of privacy" he recommended using a browser from a provider that is similarly open.

For normal work he uses Firefox "with lots of additions" to block any third parties that may monitor a user's browsing history.

And for more secure browsing and for anything where privacy is necessary he uses the free open-source browser Tor.

"Tor allows you to browse the web without revealing your identity," he said, so if you need to research a company or organisation in detail, scanning every page of their website over a period of months, for example, it helps to have that layer of anonymity.

Passphrase

The issue of password selection arises regularly and is central in protecting online data and communications. There are right and wrong ways to choose a password though.

For one 'password' is a terrible, terrible password, and 'pa$$word' is no better.

Passwords for sites like Amazon, eBay or other American companies just need to be strong enough to keep out regular hackers, Kamphuis said, as if the NSA wants access "they can just call up Amazon and get access to the server".

For the most important information however – encrypted hard drives, secure email, unlocking laptops – he recommended choosing a password of over 20 characters.

When password cracking software can guess millions of character combinations per second it makes sense that longer passwords will be harder to crack.

The problem though is that also makes them harder to remember, so a more useful and secure way to think about the concept may be in terms of a passphrase.

"It can be anything, like a line of your favourite poetry," Kamphuis said, "maybe a line from something you wrote when you were nine that no one else will know about."

The longer the phrase the more combinations hacking software needs to test to find the correct solution.

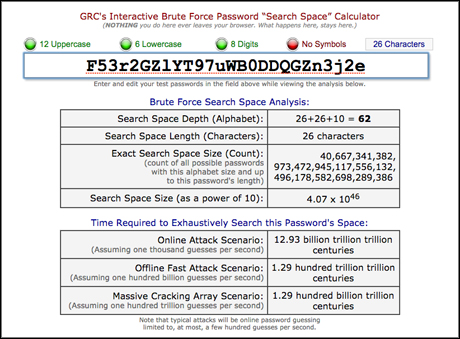

Consider the following examples, using the Gibson Research Corporation's password strength calculator.

A password like "F53r2GZlYT97uWB0DDQGZn3j2e", from a random password generator, seems very strong. Indeed it is, taking 1.29 hundred billion trillion centuries to exhaust all the combinations even when the most sophisticated software is making one hundred trillion guesses per second.

Screenshot from GRC.com

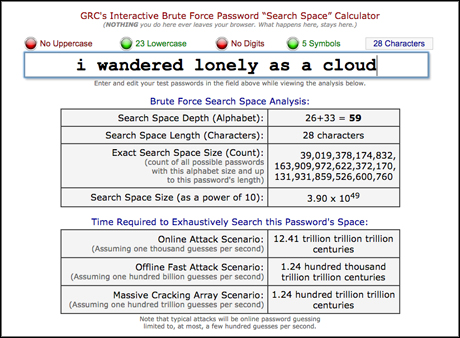

The phrase "i wandered lonely as a cloud", however, is so much easier to remember and is also more secure, taking the same software 1.24 hundred trillion trillion centuries to exhaust all possibilities.

Screenshot from GRC.com

Password-cracking software may well continue to speed up, but given the rough estimate for the last phrase is nearly 800,000 times longer than the age of the universe, you're probably safe.

Don't use a line from Wordsworth though. That's about as safe as using 'password'.

Encryption

Glenn Greenwald famously almost lost the NSA story because he initially ignored Snowden's instructions on email encryption, so if you want a story that will go down in history it makes sense to be secure.

PGP encryption was created in 1991, long enough to have been tried and tested repeatedly, said Kamphuis, to the point where it can be trusted.

With PGP encryption, you have a public key, like you public phone number, he said, and a private key.

The public key can go on Twitter biographies, business cards, websites and wherever else your work is publicised, but the private key must stored securely, as with any other sensitive information.

Then, when a source wants to send information, they will use your public key to encrypt their email that only your private key can unlock.

Kamphuis recommended the GNU Privacy Guard, an open-source version of PGP, that is simple to set up and has an active support community.

For encrypting files, data and hard drives, TrueCrypt is the best option, he said, and his free ebook released through the CIJ fully explains the process of how to encrypt files, including your PGP key, and safely locked with your 20-character password that isn't Wordsworth or "password".

Software capabilities and available fixes are constantly changing, so as a final piece of advice Kamphuis recommended getting in touch with the local hacker community stay in the loop on information security.

"If you build up a working relationship with some of these people they can provide you with a very high level of technical advice," he said. So that may be writing about a project or sharing useful contacts, but staying in touch so they can keep you up to date can prove invaluable.

A lot of the advice may seem extreme, but so are the capabilities of modern government institutions and as time and technology progress the same may be said of organised crime syndiactes.

Besides, "anybody that does anything with any device that connects information at some level is under surveillance at some point," Kamphuis said.

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).

Related articles

- Newsrewired throwback: What you learned at our previous digital journalism conference

- First-party cookies: 'Get legal help to avoid fines'

- Tip: A guide to secure communications using Signal

- Collecting first party data: Why meaningful consent should matter to publishers

- Tip: How to keep your communications secure